|

Post Office Box 1147

▪

Marblehead, Massachusetts 01945

▪ (781) 639-9709

“Every Tax is a Pay Cut ... A Tax Cut is a Pay Raise”

48 years as “The Voice of Massachusetts Taxpayers”

— and

their Institutional Memory — |

|

CLT UPDATE

Monday, January 17, 2022

Surprise Hike In Mass.

Auto Excise Coming?

Jump directly to the situation

Jump directly

to CLT's Commentary on the News

|

Most Relevant News

Excerpts

(Full news reports follow Commentary)

|

|

A new tax

on Massachusetts millionaires would add about $1.3

billion in revenue for the state, according to a new

report that analyzes the potential impact of the

proposed surtax on high-income earners that voters

will consider on the ballot in November.

Massachusetts lawmakers voted last year to put a

constitutional amendment on the 2022 ballot that

would add a 4 percent surtax on household income

above $1 million, pledging to dedicate the

additional revenue to just two areas of spending:

education and transportation.

The

analysis done by the Center for State Policy

Analysis at Tufts University offers a fresh estimate

of how much money could be generated by the tax code

change, and it largely confirms revenue projections

made last year by the Beacon Hill Institute, though

without as many dire warnings of the tax's impact on

the economy.

The report

estimates that if approved by voters the new tax

would be collected from about 21,000 state

taxpayers, or less than 1 percent of all households

in the state, who earn about 22 percent of all

taxable income in Massachusetts. Using state and

federal data, the center estimated that 2,000

households earned more $5 million in 2019 totaling

11 percent of all income in the state.

The

projection takes into account the likelihood that

some high-earners could leave Massachusetts as a

result of the policy, while others will engage in

"tax avoidance" strategies to lower their tax

burden.

"Some

high-income residents may relocate to other states,

but the number of movers is likely to be small," the

report concludes, relying on research done in other

states like California and regions of Spain that

suggest Massachusetts could lose 500 families and

about $100 million in tax revenue from

relocation....

Moves out

of state and tax avoidance measures are projected to

reduce the state's overall revenue from the income

surtax by 35 percent in 2023, down from a possible

$2.1 billion if no behavioral changes were accounted

for. The report attributed about $670 million of the

lost revenue to tax avoidance.

"Even

accounting for that, it still seems like an approach

that will raise substantial revenue and in a way

that advocates say it will from higher earners in a

progressive way," said Evan Horowitz, executive

director of the Center for State Policy Analysis.

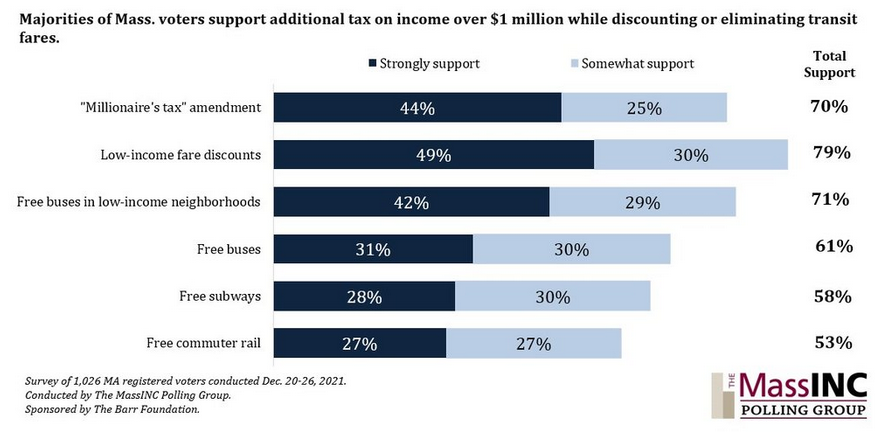

A new

poll released Thursday from the MassINC Polling

Group found that 70 percent of registered voters

support the ballot question, including 44 percent

who said they strongly support a surtax that would

be spent on transportation and education. Only 10

percent of those surveyed said they were still

unsure....

One

unknown, the report acknowledges, is how the money

will be invested.

While the

ballot question states that it must be spent on

education and transportation, all state spending is

still subject to appropriation by the Legislature

and there's the risk that the money, once pooled

together with other revenues, will be used to

replace existing spending instead of solely to

increase investments.

State

House News Service

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Study Pegs Wealth Surtax Haul At

$1.3 Billion

Relocations, Tax Avoidance Will Reduce Take By $670

Million

CLICK HERE OR IMAGE ABOVE TO WATCH

The

Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance held a press

conference Thursday afternoon to express

opposition to a 4 percent surtax on incomes

above $1 million that is slated to go before

voters in November in the form of a

constitutional amendment. [Screenshot]

Opponents

of a plan to change the constitution to allow a 4

percent surtax on household incomes above $1 million

pushed back Thursday on one finding from a new study

and refuted suggestions that the new revenue would

be spent only on transportation and education.

Residents

will vote on the measure, dubbed the "fair share

amendment" by proponents, during the November

election after legislators voted 159-41 in June 2021

to place it on the ballot. A new poll released by

the MassINC Polling Group Thursday showed 70 percent

of registered voters in support of the question....

At a

virtual press conference Thursday hosted by the

Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, lawmakers and

researchers suggested the Legislature could decide

to allocate revenue from the amendment to different

areas.

"The state

constitution specifically prohibits earmarking

funds, revenue," said Rep. David DeCoste

(R-Norwell). "Since the Legislature appropriates

revenue, only the Legislature will have the final

word in terms of what will be spent and for what.

The idea that these funds will somehow be fenced for

transportation and education is really unrealistic."

The

amendment's language says revenues from the surtax

can only be used "for quality public education and

affordable public colleges and universities, and for

the repair and maintenance of roads, bridges and

public transportation."

But

opponents argue that even within those categories,

money can be "fungible." DeCoste called education

and transportation broad categories.

"Pensions

could be considered to fall under these categories,"

he said. "And for that reason, I think this is a bad

initiative and I will actively oppose it." ...

Rep.

Colleen Garry (D-Dracut) said the amendment does not

guarantee dollars will head to education and

transportation.

"I think

that it's extremely important that the truth be put

out there that we cannot assure anyone that going

forward, this money will be always spent on

education and transportation," she said. "It would

be up to whatever Legislature is in at that time to

make that determination. And they can always say, I

wasn't there when the promise was made, so I didn't

make the promise."

State

House News Service

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Wealth Surtax Opponents

State Their Case

Garry: Future Lawmakers Can Say "I Didn't Make That

Promise"

Opponents

of a millionaires’ tax before voters this fall say

the $1.3 billion in new annual income will cost Bay

Staters 9,000 lost jobs and drive out up to 4,000

high-earning families at a time when Massachusetts

is already “flush with cash.”

Massachusetts voters will decide on the measure,

dubbed the “fair share amendment” by proponents, in

the November election. It would add a 4% surcharge

on incomes over $1 million.

This is

the Legislature’s seventh attempt to pass a wealth

tax, but a new poll released by the MassINC Polling

Group Thursday showed this time it’s likely to

stick, with 70% of registered voters in support of

the question....

Opponents

also pushed back on ballot question language saying

revenue generated by the tax would be earmarked for

education and transportation funding.

“The state

constitution specifically prohibits earmarking

funds, revenue,” said Rep. David DeCoste, R-Norwell.

“Since the Legislature appropriates revenue, only

the Legislature will have the final word in terms of

what will be spent and for what. The idea that these

funds will somehow be fenced for transportation and

education is really unrealistic.”

The

Boston Herald

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Massachusetts

millionaires’ tax could generate $1.3 billion,

but with ‘high’ cost to jobs, taxable income

Legislative and Baker administration budget writers

are projecting that state tax revenue will grow by

2.7 percent next fiscal year, from the $35.948

billion they are now expecting the state to collect

in fiscal 2022.

Administration and Finance Secretary Michael

Heffernan and Ways and Means Committee chairs Sen.

Michael Rodrigues and Rep. Aaron Michlewitz are

required to jointly develop a revenue forecast each

year, which lawmakers and Gov. Charlie Baker use in

crafting their spending plans. Baker, who makes the

first volley in the annual budgeting process, is due

to file his bill by Jan. 26.

The trio

on Friday announced a consensus revenue forecast of

$36.915 billion for the fiscal year beginning July

1, which would make a maximum of $29.783 billion in

tax revenue available for the fiscal 2023 budget

after accounting for statutorily required transfers.

In conjunction with the announcement, Heffernan said

he is revising this year's revenue projection upward

by $1.548 billion based on year-to-date collections

and economic data. As of December, the state had

collected more than $17.8 billion in taxes so far

this fiscal year.

State

House News Service

Friday, January 14, 2022

Agreement on Tax Revenue

Estimate Kicks Off Budget Cycle

REVENUE

COMMITTEE: Revenue Committee holds a virtual hearing

on 66 bills related to the environment and farms --

including bills that deal with agricultural land or

climate change adaptation -- and sales and excise

taxes. The agenda includes bills that would reduce

the state's 6.25 percent sales tax to 5 percent, and

others that propose tax exemptions for gun safes and

trigger locks, zero-emission commercial vehicles,

certain medical supplies, purchases of Energy

Star-rated products and hybrid or electric cars on

Earth Day, and electric-vehicle chargers.

State

House News Service

Friday, January 13, 2022

Advances: Week of Jan. 16, 2022

An Act

relative to lowering the sales tax to 5%

By Mr.

Lombardo of Billerica, a petition (accompanied by

bill, House, No. 2992) of Marc T. Lombardo for

legislation to lower the sales tax to five percent.

Revenue.

Bill H.2992

SECTION 1.

Section 2 of Chapter 64H of the General Laws, as

appearing in the 2008 Official Edition, is hereby

amended by striking “6.25 per cent” and replacing it

with “5 per cent”.

SECTION 2.

Section 2 of Chapter 64I of the General Laws, as

appearing in the 2008 Official Edition, is hereby

amended by striking “6.25 per cent” and replacing it

with “5 per cent”.

The

Washington Post published an article on January 9

critical of the Iowa Senate for a new policy that

requires reporters to now observe senate proceedings

from a viewing gallery, as is customary in most

other state legislatures. Journalists had previously

been permitted on the floor of the Iowa Senate,

something unique to the Hawkeye State. Yet, while

the Washington Post deems this rule change in Iowa

worthy of national coverage, the paper hasn’t

published anything on what is arguably the least

transparent state legislative body in country: the

Massachusetts statehouse.

In 1766, a

decade before the Declaration of Independence was

written, the Massachusetts House of Representatives

constructed a viewing gallery, the first to do so

among the thirteen colonial legislatures, for the

public to witness debates and legislative

proceedings. In his latest book, “Power & Liberty,”

historian Gordon Wood described the creation of a

public gallery in the Massachusetts statehouse as

“an important step in the democratization of

American political culture.”

Yet,

whereas Massachusetts had been a historical leader

in transparency in government even prior to the

nation’s founding, today the commonwealth is

arguably the least transparent state government in

the entire United States....

“There is

no legislative body in America as opaque as the

Massachusetts Legislature,” says Paul Craney,

spokesman for the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, a

non-partisan taxpayer organization. “They have

gotten away with passing billion dollar budgets

without a vote, passing new taxes without a vote,

making some of their votes not available to the

public.” ...

Massachusetts legislators have even gone so far as

to refuse to implement ballot measures that have

been approved by voters. In 2000, for example,

Massachusetts residents voted in favor of Question

4, a ballot measure that rolled back the state

income tax rate from 5.95% to 5.0%. Yet state

lawmakers decided to delay implementation of that

tax rollback, despite the fact that 56% of

Massachusetts cast ballots in favor.

“Instead,

Beacon Hill dropped the tax rate to 5.3% and passed

a law conceding the rest — but only in small doses,

and only if the state met certain financial

targets,” explained Governing Magazine. “The first

of those steps didn’t come for another decade.” ...

Though the

income tax cut approved by Massachusetts voters was

finally implemented by lawmakers, albeit 20 years

later, it’s not lost on many Massachusetts residents

that state lawmakers refused to carry out the will

of voters so that they could tax more of their

income. "And to think about the billions of dollars

that the state government has siphoned from

taxpayers' wallets during all those years," said

Chip Ford, executive director of Citizens for

Limited Taxation, the organization that led the

campaign in favor of Question 4 back in 2000. "It's

disgraceful." ...

If the

Washington Post and other national outlets are

looking for a statehouse that is lacking in

government transparency, they would do well to turn

their attention to the golden dome on Boston’s

Beacon Hill.

Forbes

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

In Massachusetts, Once A Leader In

Government Transparency,

Key Votes Are Hidden From The Public

By Patrick Gleason

Kentuckians could see property taxes on their cars

and trucks leap this year when renewing their

vehicle registrations.

Like with

many rising prices these days, COVID is to blame.

Supply shortages caused by the pandemic have made

new vehicles scarce, pushing buyers to previously

owned options, which in turn has increased used car

values.

In

Kentucky, where property tax is assessed each year

on the value of motor vehicles, this spells a likely

uptick in what people will owe.

For

instance, Wayne County resident Randy Bauer was told

by local officials that his 2019 Toyota 4Runner,

which he bought in late 2018 for about $38,000, has

a 2022 valuation of around $42,000.

“I’ve

never had vehicles appreciate, especially when they

appreciate over what you’ve paid for them brand

new,” Bauer told Reader’s Watchdog, adding he’ll owe

just under $500 in taxes.

Car

values, overall, are jumping about 40% this year

compared to last year, according to a letter sent by

the Kentucky Department of Revenue to county

officials.

The state

updates these trade-in values yearly through its

vendor, market research firm J.D. Power.

In the

letter, the revenue department cites well-documented

recent trends in the automobile industry, including

new vehicle production constraints — due to computer

chip shortages, for one — increased new vehicle

prices and limited used car supply, as factors

contributing to the jump in used car prices.

Bauer, who

moved to Kentucky last year, said it seemed unfair

to him to be taxed on an inflated value of his

vehicle.

“They

ought to be able to leave it the way it is and not

raise it,” Bauer said....

In

response to the likely tax increase, as of Jan. 12,

Kentucky legislators had filed at least four bills

addressing vehicle property taxes....

In 2020, a

2019 Toyota Corolla was valued at $13,450. Last

year, it dropped to $12,900 but this year

skyrocketed 48% to $19,050.

Based on a

Jefferson County average of $13.50 in taxes per

$1,000 of value, that means the tax on the Corolla

last year would have been $174 compared to $257 in

2022.

The

Courier Journal

Louisville, KY

Friday, January 14, 2022

Property taxes on

Kentuckians' cars and trucks are jumping |

|

It was another typical

crazy week at CLT, first putting together and delivering our

testimony for the

Joint Committee on Revenue hearing on Tuesday in which CLT

supported H.2881, a

long-overdue revision of the onerous Massachusetts estate tax.

Next came the Tufts University release of its Center for State

Policy Analysis

report on the effects the sixth graduated income tax

(aka, the "Millionaire's Tax," aka, the "Fair Share Amendment") if

the state constitutional amendment should be approved by the voters

in November.

That report was

accompanied on the same morning by a new

MassINC poll showing how wildly popular "taxing the rich" has

not-so-surprisingly become, with 70% of its respondents across the

board of

all

ages, stripes and persuasions supposedly in favor of it

— in fact the same respondents to the same

poll also strongly or somewhat support free or discounted public

transportation too.

Tax

hikes on others, more freebies for me. Do I perceive a pattern

in respondents and the the polling company's selection? Just

asking.

Coincidentally of course, both the poll and the report were released

on the same morning. The report by the Center for State

Policy Analysis at Tufts University

concerning the upcoming graduated income tax ballot question noted:

WHO WOULD PAY?

While very few households in Massachusetts earn over $1 million

in any given year, they account for a substantial share of total

income in the state.

In 2019 — the last year for which we have complete data — there

were 21,000 state taxpayers with incomes of more than $1

million, amounting to just 0.6 percent of all households. Yet

those households earned 22 percent of all taxable income in

Massachusetts.

The farther you go up the income ladder, the starker this

imbalance. Combining state and federal data, we estimate that

Massachusetts had around 2,000 households earning above $5

million in 2019, but those 0.06 percent of taxpayers garnered 11

percent of all income.

Salaries and paychecks comprise about a third of the income for

these million-dollar-a-year households; a similar amount comes

from capital gains, and another 20 percent is passed through

from business income.

Racial

inequities among big earners are trickier to pin down, as

publicly available tax data doesn’t generally capture details

about race or ethnicity. But separate surveys suggest that

non-Hispanic whites comprise nearly 90 percent of all

million-dollar earners in Massachusetts, and that white families

are three to four times more likely to earn seven figures than

Asian, Hispanic, or Black families.

Notice that according to

this report, "In 2019 — the last year for which we have complete

data — there were 21,000 state taxpayers with incomes of more than

$1 million, amounting to just 0.6 percent of all households.

Yet those households earned 22 percent of all taxable income in

Massachusetts."

Pay close attention here

folks. Viewed slightly differently, this translates to 21,000

state taxpayers — "amounting to just

0.6 percent of all households" — are

already paying the standard 5% income tax on a disproportionate

22 percent of all income taxes extracted by the state from all the

productive in Massachusetts. And that's still not

enough for The Takers and more never is.

In quick response to the

two morning releases and news reports on them we Grad Tax opponents

leaped into action, thanks to Paul Craney and MassFiscal setting up

a Zoom virtual news conference that noon.

CLICK HERE OR IMAGE ABOVE TO WATCH

Rep. Colleen Garry is a Democrat from Dracut.

Paul Craney introduced her as the first opposition speaker at our

press conference. She warned that the constitutional amendment

will not and cannot guarantee the revenue it proposes to raise will

all go to education and transportation as its supporters assert.

"I think

that it's extremely important that the truth be put

out there that we cannot assure anyone that going

forward, this money will be always spent on

education and transportation," she said. "It would

be up to whatever Legislature is in at that time to

make that determination. And they can always say, I

wasn't there when the promise was made, so I didn't

make the promise."

David Tuerck of the Beacon

Hill Institute spoke next then it was my turn. My first words

(at 11:58 minutes in) were in support of Rep. Garry's assertion.

I reminded all that legislative promises were made to be broken and

referenced the "temporary, 18-month" income tax hike of 1989 that

remained until CLT's successful 2000 ballot question finally forced

it back to 5 percent, finally thirty years later in 2020.

On June 23, 1997 when

called out on that broken promise eight years after it was made,

then-House Speaker Thomas Finneran responded:

"Maybe somebody at

the time said, 'Well, gee, maybe we should or maybe we could

consider rolling it back,' but Barbara [Anderson] has been

around long enough to know statements come and go and language

is statutory. I don't know how someone could attach

legitimacy to a comment made in the hall, in a hearing, or even

on the House floor."

CLT used

that quote by the then-House Speaker surrounded by

excerpts from contemporaneous 1989 newspaper reports

like "Dems eyeing temporary state income tax hike"

in which that legislative promise was prominently

repeated in a

flyer and newspaper ad we created during our

successful ballot question campaign.

Too many politicians lie

too often — case closed.

We were reminded again of

that 2000 ballot question campaign and the Legislature's

unscrupulous cupidity on Wednesday in an article published in

Forbes ("In Massachusetts, Once A

Leader In Government Transparency, Key Votes Are Hidden From The

Public") by Patrick Gleason of Americans for Tax Reform.

Here's an excerpt from it:

. . . Massachusetts

legislators have even gone so far as to refuse

to implement ballot measures that have been

approved by voters. In 2000, for example,

Massachusetts residents voted in favor of

Question 4, a ballot measure that rolled back

the state income tax rate from 5.95% to 5.0%.

Yet state lawmakers decided to delay

implementation of that tax rollback, despite the

fact that 56% of Massachusetts cast ballots in

favor.

“Instead, Beacon Hill

dropped the tax rate to 5.3% and passed a law

conceding the rest — but only in small doses,

and only if the state met certain financial

targets,” explained Governing Magazine. “The

first of those steps didn’t come for another

decade.” ...

Though the income tax cut

approved by Massachusetts voters was finally

implemented by lawmakers, albeit 20 years later,

it’s not lost on many Massachusetts residents

that state lawmakers refused to carry out the

will of voters so that they could tax more of

their income. "And to think about the billions

of dollars that the state government has

siphoned from taxpayers' wallets during all

those years," said Chip Ford, executive

director of Citizens for Limited Taxation,

the organization that led the campaign in favor

of Question 4 back in 2000. "It's disgraceful."

...

If the Washington Post and

other national outlets are looking for a

statehouse that is lacking in government

transparency, they would do well to turn their

attention to the golden dome on Boston’s Beacon

Hill.

Then

to top off the crazy week this surfaced in Kentucky which appears

will affect Massachusetts as well.

Kentucky motorists were just blindsided by a huge and unexpected

hike in its "motor vehicle tax" — the

equivalent of the Massachusetts auto excise (tax). Kentuckians

are

shocked, but fortunately the state's General Assembly (state legislature) is

in its brief annual session and legislators have already filed four

bills to turn back the surprise increase.

(The

Kentucky General Assembly convenes in regular session on the first

Tuesday after the first Monday in January for 60 days in

even-numbered years and for 30 days in odd-numbered years. The

Kentucky Constitution mandates that a regular session be completed

no later than April 15 in even-numbered years and March 30 in

odd-numbered years.)

You

know me — I can't let something like this pass without questioning

it, digging in to uncover if and how it might similarly impact Bay

State motorists and taxpayers.

What

I've found and present here is an advance warning to all, an alert. This

dynamic (what I call "Bidenflation") I strongly suspect will affect

the Massachusetts auto excise taxpayers as well, though I haven't

found any mention of it anywhere in Boston news

reports or my research — yet.

The

similarities are too close to not have the same effect.

At least in Kentucky there's a taxpayer-friendly supermajority in

its General Assembly that's already moving to stop the hike.

The Courier Journal (Louisville, KY) reported on

Friday ("Property taxes on Kentuckians'

cars and trucks are jumping"):

Kentuckians could see

property taxes on their cars and trucks leap

this year when renewing their vehicle

registrations.

Like with many rising

prices these days, COVID is to blame. Supply

shortages caused by the pandemic have made new

vehicles scarce, pushing buyers to previously

owned options, which in turn has increased used

car values.

In Kentucky, where property

tax is assessed each year on the value of motor

vehicles, this spells a likely uptick in what

people will owe....

Car values, overall, are

jumping about 40% this year compared to last

year, according to a letter sent by the Kentucky

Department of Revenue to county officials....

Bauer, who moved to

Kentucky last year, said it seemed unfair to him

to be taxed on an inflated value of his vehicle.

“They ought to be able to

leave it the way it is and not raise it,” Bauer

said....

In response to the likely

tax increase, as of Jan. 12, Kentucky

legislators had filed at least four bills

addressing vehicle property taxes....

In 2020, a 2019 Toyota

Corolla was valued at $13,450. Last year, it

dropped to $12,900 but this year skyrocketed 48%

to $19,050.

Based on a Jefferson County

average of $13.50 in taxes per $1,000 of value,

that means the tax on the Corolla last year

would have been $174 compared to $257 in 2022.

WHAS TV-11

(Louisville, KY) reported on the tax ("Kentucky's

car tax: How fair is it?") and how it's

calculated:

“On our projection report,

I think it was about $140 million.” Cathey

Thompson, the Department of Revenue State

Evaluation Division Director, said.

The county clerk gets four

percent for collection services on the local

level.

For example, a 2016 Mini

Cooper assessed at just over $19,000, a 2010

Ford Explorer at $5,650, and a 2006 Hyundai

Tucson at an even $2,600.

“It's ‘fair cash’ value,”

Thompson explained.

The Commonwealth's

Constitution (Section 172) defines ‘fair cash

value’ as the "price it would bring at a fair

voluntary sale" which the Kentucky Department of

Revenue interprets as a NADA ‘clean trade’.

Values based on the ‘clean

trade’ condition of a vehicle as of Jan. 1.

Those values defined by the

$124,000 annual subscription the Department has

with the "National Auto Dealers Association

(NADA)."

Here is the definition of a

clean trade from a NADA book: ’Clean’ represents

no mechanical defects and passes all necessary

inspections with ease. Paint, body, and wheels

may have some minor surface scratching with a

high gloss finish.

In Kelley Blue Book (KBB),

‘good’ condition is closest to NADA’s definition

of ‘clean trade’ condition.

But even in KBB’s ‘very

good’ condition, the trade price is

significantly disproportionate with NADA but

more in line with values on Cars.com which uses

Black Book....

Thompson said she is not

aware of the NADA giving them over inflated

prices.

“From what I’ve been told

that NADA more closely represents the ‘fair

cash’ value, which is a sale between a willing

buyer and a willing seller,” Thompson said....

Used car director Brian

Ubelhart has assessed thousands of cars and

believes it is hard for most vehicles on the

road to meet the ‘clean trade’ standard.

“It's almost impossible for

any car with several years and tens-of-thousands

of miles on it to be a ’clean trade’,” Ubelhart

said....

"In the 'clean' to

'excellent' condition, you're looking at 5% of

the cars that we look at," Ubelhart explained,

“most of the time it's just unrealistic”.

Ubelhart said he believes

NADA has always overvalued vehicles....

The Kentucky Department of

Revenue pays NADA (National Automobile Dealers

Association) to provide it with an annual list

of assessments for each vehicle registered in

the commonwealth.

NADA is one of several

services car dealers, and in this case state

government, can use to determine vehicle values.

The Kentucky Department of

Revenue is required by the Commonwealth

Constitution Section 172 to assess property tax

"at its fair cash value, estimated at the price

it would bring at a fair voluntary sale".

NADA’s “Clean Trade-In”

value is the standard the state uses to tax.

The Massachusetts

Secretary of State's office publishes "Motor Vehicle Excise

Information" both on

its website and in

booklet

format. Here's the relevant excerpt regarding how it's

calculated:

Under MGL Chapter

60A, all Massachusetts residents who own and register a motor

vehicle must annually pay a motor vehicle excise. Also,

under MGL Chapter 59, Section 2, it is important to note that

every motor vehicle, whether registered or not, is subject to

taxation, either as excise or personal property, for the

privilege of road use, whether actual or future. The

excise is levied by the city or town where the vehicle is

principally garaged and the revenues become part of the local

community treasury....

Bill Computation

An excise at

the rate of $25 per one thousand dollars of valuation (effective

1/1/81) is levied on each motor vehicle. Information on

the value of a motor vehicle is accessed electronically through

a data bank complete with valuation figures. Different

sources provide the valuation figures depending upon whether the

motor vehicle is an automobile, a truck, a motorcycle, or a

trailer. For example, automobile valuations are derived

from figures published in the National Automobile Dealers

Association Official Used Car Guide (NADA), to which the

Registry has electronic access. Most public libraries

have copies of NADA and other motor vehicle official guides.

Note the effective date when the rate of $25 per one thousand dollars of valuation

became law: January 1, 1981. That was the direct result

of CLT's Proposition 2½. Along with

limiting the increase of property taxes Prop 2½ also reduced the auto

excise (tax) from $66 per $1,000 valuation to $25 per $1,000.

(How

much does that one tax cut alone save you every year?)

• Both Kentucky and

Massachusetts use the National Automobile Dealers Association

Official Used Car Guide (NADA) to calculate their respective auto

excise/motor vehicle taxes.

• NADA is

automatically adding the 40% inflation factor on new and used

vehicles to what it's providing state subscribers of its service —

which includes both Kentucky and Massachusetts.

• Kentucky has begun

to automatically build those NADA-provided inflation increases into

its motor vehicle tax bills.

• Does anybody

think the same won't happen in Massachusetts as well?

I'll be digging deeper in

the days ahead. The least CLT can do is spread the word that

it's coming, as Paul Revere did.

— UPDATE —

Correction

Since this was sent out to

members as an e-mailed CLT Update earlier today it was brought to my

attention by two of them that in fact Massachusetts calculates its

auto excise tax by a different, newer formula. Upon reading

the above alert both John G. of Whitman, and former chairman of

CLT's board of directors Attorney Paul Nicolai, contacted me with

the correction. Paul told me: "The Massachusetts auto

excise tax used to be calculated on NADA Blue Book. It's no

longer the case. It is now calculated on MSRP."

Here's the excerpt from

the Secretary of State's website detailing how the Massachusetts

auto excise tax is calculated today:

For a detailed explanation

with examples also provided by the Secretary of State's office see:

Calculation Of The Excise Amount

The newer state

calculation is based on a percentage of the "manufacturer's list

prices for vehicles in the year of manufacturer" (also called the

Manufacturer's Suggest Retail Price, or the MSRP) and the age of the

vehicle being taxed.

"The excise tax law

... establishes its own formula for valuation for state tax

purposes whereby only the manufacturer's list price and the age

of the motor vehicle are considered."

My thanks to John and Paul

for the quick correction.

I then wondered if, since

the cost of a new vehicle today (if you can find one) has been much

higher due to shortages than the cost of last year’s new models,

will that have any impact on the percentage trickle-down effect in

ensuing years?

John replied: "Some

cars are now being sold at a “premium” rather than a “discount” from

the MSRP. If somebody pays, say, $4,000 over MSRP, will the

excise tax be based on the MSRP or the sales price? I suspect

that the answer is “the MSRP” but I don’t know. Probably a

question better directed to the Dept. of Revenue.

"Certainly, to the extent

that the MSRP increases from one model year to the next, that

results in an increase in the excise tax. But that’s different

from the atypical price increases that are being caused by the

shortages now."

I suppose my question is a

hypothetical one for down the road.

At least my greatest

concern has been removed, that Massachusetts was caught up in the

same unexpected situation as Kentucky (and likely a few of the other

states that impose a motor vehicle/auto excise tax).

Massachusetts has avoided that problem by having revised its excise

tax calculation in the past. Hurrrah!

|

|

|

|

Chip Ford

Executive Director |

|

|

State House News

Service

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Study Pegs Wealth Surtax Haul At $1.3 Billion

Relocations, Tax Avoidance Will Reduce Take By $670 Million

By Matt Murphy

A new tax on Massachusetts millionaires would add about $1.3

billion in revenue for the state, according to a new report

that analyzes the potential impact of the proposed surtax on

high-income earners that voters will consider on the ballot

in November.

Massachusetts lawmakers voted last year to put a

constitutional amendment on the 2022 ballot that would add a

4 percent surtax on household income above $1 million,

pledging to dedicate the additional revenue to just two

areas of spending: education and transportation.

The analysis done by the Center for State Policy Analysis at

Tufts University offers a fresh estimate of how much money

could be generated by the tax code change, and it largely

confirms revenue projections made last year by the Beacon

Hill Institute, though without as many dire warnings of the

tax's impact on the economy.

The report estimates that if approved by voters the new tax

would be collected from about 21,000 state taxpayers, or

less than 1 percent of all households in the state, who earn

about 22 percent of all taxable income in Massachusetts.

Using state and federal data, the center estimated that

2,000 households earned more $5 million in 2019 totaling 11

percent of all income in the state.

The projection takes into account the likelihood that some

high-earners could leave Massachusetts as a result of the

policy, while others will engage in "tax avoidance"

strategies to lower their tax burden.

"Some high-income residents may relocate to other states,

but the number of movers is likely to be small," the report

concludes, relying on research done in other states like

California and regions of Spain that suggest Massachusetts

could lose 500 families and about $100 million in tax

revenue from relocation.

The reason for the small number of relocations, the report

suggests, is that wealthy families tend to be connected to

their communities with kids in schools and other ties, while

those that do move are likely to be the wealthiest of the

payers. Some taxpayers may simply shift their permanent

residence out of state, while remaining in Massachusetts for

much of the year, the report contends.

Moves out of state and tax avoidance measures are projected

to reduce the state's overall revenue from the income surtax

by 35 percent in 2023, down from a possible $2.1 billion if

no behavorial changes were accounted for. The report

attributed about $670 million of the lost revenue to tax

avoidance.

"Even accounting for that, it still seems like an approach

that will raise substantial revenue and in a way that

advocates say it will from higher earners in a progressive

way," said Evan Horowitz, executive director of the Center

for State Policy Analysis.

A new poll released Thursday from the MassINC Polling Group

found that 70 percent of registered voters support the

ballot question, including 44 percent who said they strongly

support a surtax that would be spent on transportation and

education. Only 10 percent of those surveyed said they were

still unsure.

While the Center for State Policy Analysis arrived at

similar projections as a study done by the more conservative

Beacon Hill Institute last year, Horowitz said he does not

see the same risk to the state's economy.

Both independent estimates are lower than the $1.6 billion

to $2.2 billion projected by the Department of Revenue in

2015, though the state agency did not attempt to factor in

behavorial changes such as relocation.

"Our static estimate is very similar to their," Horowitz

said of DOR.

The Beacon Hill Institute projected the wealth surtax would

generate $1.23 billion in new taxes in 2023, but also said

it would cost the state 9,329 private sector jobs in the

first year and reduce the number of working households by

4,388, mostly due to high earners leaving Massachusetts for

lower cost states. The think-tank forecast a $431 million

decrease in gross state product, a $931 million decrease in

real disposable income and $7 million in lost investments.

Horowitz, however, said the impact on the Massachusetts

economy is likely to be "small."

"The reasons we come to similar numbers is totally

different. We don't see the substantial risk from depressed

economic activity and large number of people moving out of

state," Horowitz said. "It's chiefly an accounting issue,

not an economic one."

The report attributes its more optimistic economic forecast

to the relatively small size of the tax increase compared to

the overall economy and the fact that while avoidance

measures will decrease the state's tax haul on paper it will

not reduce significantly the amount of wealth available to

be spent and invested in the economy.

"Critics of the proposal sometimes argue that it would cost

jobs and blunt economic growth. But just as decades of

research on tax cuts have failed to reveal large stimulative

effects, tax increases of this size are unlikely to

meaningfully dampen economic activity," the report says.

One unknown, the report acknowledges, is how the money will

be invested.

While the ballot question states that it must be spent on

education and transportation, all state spending is still

subject to appropriation by the Legislature and there's the

risk that the money, once pooled together with other

revenues, will be used to replace existing spending instead

of solely to increase investments.

CLICK HERE OR IMAGE ABOVE TO WATCH

The

Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance held a press

conference Thursday afternoon to express

opposition to a 4 percent surtax on incomes

above $1 million that is slated to go before

voters in November in the form of a

constitutional amendment. [Screenshot]

State House News

Service

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Wealth Surtax Opponents State Their Case

Garry: Future Lawmakers Can Say "I Didn't Make That Promise"

By Chris Van Buskirk

Opponents of a plan to change the constitution to allow a 4

percent surtax on household incomes above $1 million pushed

back Thursday on one finding from a new study and refuted

suggestions that the new revenue would be spent only on

transportation and education.

Residents will vote on the measure, dubbed the "fair share

amendment" by proponents, during the November election after

legislators voted 159-41 in June 2021 to place it on the

ballot. A new poll released by the MassINC Polling Group

Thursday showed 70 percent of registered voters in support

of the question.

In advocating for the constitutional amendment, supporters

have said it could raise $2 billion per year that would be

directed towards education and transportation needs. Among

other things, they have pointed to a need to fund the

Student Opportunity Act, a law crafted to direct $1.5

billion to K-12 schools over seven years.

A study released Wednesday from the Center for State Policy

Analysis at Tufts University showed the amendment would draw

in about $1.3 billion in revenue for the state. The $700

million difference accounts for some high-earning people

leaving the state and use of "tax avoidance" strategies to

lower tax burdens.

At a virtual press conference Thursday hosted by the

Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, lawmakers and researchers

suggested the Legislature could decide to allocate revenue

from the amendment to different areas.

"The state constitution specifically prohibits earmarking

funds, revenue," said Rep. David DeCoste (R-Norwell). "Since

the Legislature appropriates revenue, only the Legislature

will have the final word in terms of what will be spent and

for what. The idea that these funds will somehow be fenced

for transportation and education is really unrealistic."

The amendment's language says revenues from the surtax can

only be used "for quality public education and affordable

public colleges and universities, and for the repair and

maintenance of roads, bridges and public transportation."

But opponents argue that even within those categories, money

can be "fungible." DeCoste called education and

transportation broad categories.

"Pensions could be considered to fall under these

categories," he said. "And for that reason, I think this is

a bad initiative and I will actively oppose it."

Sen. Jason Lewis, a co-sponsor of the amendment in the

Legislature, said he "fully expects" future Legislatures to

spend the additional funding on education and

transportation.

"The language of the ballot question, which again, will be

in our state constitution, says very clearly that this money

needs to be spent only on education and transportation," he

told the News Service. "I think that gives very clear

direction to future Legislatures and governors."

Rep. Colleen Garry (D-Dracut) said the amendment does not

guarantee dollars will head to education and transportation.

"I think that it's extremely important that the truth be put

out there that we cannot assure anyone that going forward,

this money will be always spent on education and

transportation," she said. "It would be up to whatever

Legislature is in at that time to make that determination.

And they can always say, I wasn't there when the promise was

made, so I didn't make the promise."

In arguing against the ballot question, MassFiscal spokesman

Paul Craney pointed to a June 2018 Supreme Judicial Court

ruling that prohibited an earlier version of the income

surtax from appearing on the ballot. Justices ruled the

question -- as written at the time -- improperly mixed two

different spending areas and a significant change in tax

policy.

The court said voters who supported the tax but did not

support earmarking funds for education or transportation and

voters who wanted to designate funds to those areas but did

not back the tax were placed in untenable positions.

Speakers at the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance press

conference also warned that high-earning individuals may end

up leaving the state as a result of the 4 percent tax on

incomes above $1 million.

The Tufts University study acknowledged that some

high-income residents may relocate, "but the number of

movers is likely to be small." The report concludes that 500

families could end up leaving the state and Massachusetts

could lose roughly $100 million in tax revenue from

relocation.

Rep. Nicholas Boldyga (R-Southwick) said top earners in

Massachusetts "are going to flee the state in droves" as a

result of the amendment and "we're going to be left in a

much worse position."

"Everyone here in the commonwealth can agree upon that when

the wealthiest of the residents of our state see the biggest

tax increases, they are the people that actually have the

resources to pack up and establish residency elsewhere," he

said.

Lewis believes this line of thinking is just a scare tactic.

"That's always been a scare tactic that opponents of the

fair share amendment have used, that this would drive lots

of people to leave Massachusetts and I think that's not

borne out by the experience in other states and other

countries," Lewis said.

Rep. Marc Lombardo (R-Billerica) said Massachusetts is flush

with cash as the state had over $5 billion in revenue above

benchmark last fiscal year and is billions above benchmark

halfway through this fiscal year.

"Massachusetts has money coming in, we have more than enough

to fund these critical programs that we need without raising

taxes on the hard-working families," he said.

The Boston

Herald

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Massachusetts millionaires’ tax could generate $1.3 billion,

but with ‘high’ cost to jobs, taxable income

By Erin Tiernan

Opponents of a millionaires’ tax before voters this fall say

the $1.3 billion in new annual income will cost Bay Staters

9,000 lost jobs and drive out up to 4,000 high-earning

families at a time when Massachusetts is already “flush with

cash.”

Massachusetts voters will decide on the measure, dubbed the

“fair share amendment” by proponents, in the November

election. It would add a 4% surcharge on incomes over $1

million.

This is the Legislature’s seventh attempt to pass a wealth

tax, but a new poll released by the MassINC Polling Group

Thursday showed this time it’s likely to stick, with 70% of

registered voters in support of the question.

A new study from The Center For State Policy Analysis at

Tufts University found it could generate $1.3 billion in new

tax revenue annually.

That’s less than the $2 billion predicted by a state

Department of Revenue in a report several years ago but

still a “meaningful amount of money” for Massachusetts,

while only hiking taxes on the Bay State’s top 0.6% of

earners, the study states.

“The millionaires’ tax also could have some serious side

effects if top earners opt to leave the state or shield

their income to avoid paying,” the Tufts University study

points out, saying “the number of movers is likely to be

small.”

The report concludes that 500 families could end up leaving

the state and Massachusetts could lose roughly $100 million

in tax revenue from relocation.

David Tuerck with the Beacon Hill Institute produced it’s

own financial predictions for the so-called millionaires’

tax. While its prediction that it would raise about $1.2

billion in new annual revenue is close to the Tufts figure,

Tuerck said “that’s the only similarity.”

Tuerck said the tax hike would “kill” 9,000 jobs in the

first year and cause up to 4,000 high-earning Massachusetts

families to relocate — a “much bigger” economic hit than the

Tufts report predicts.

State Rep. Nicholas Boldyga, R-Southwick, said top earners

in Massachusetts “are going to flee the state in droves” to

avoid the tax, leaving the commonwealth “in a much worse

position.”

State Rep. Marc Lombardo, R-Billerica, said “the reality is

that Massachusetts is flush with cash,” arguing

Massachusetts has no need to raise taxes on the wealthy with

so much green flowing in already.

The state had over $5 billion in revenue above benchmark

last fiscal year and is already billions above benchmark

halfway through this fiscal year. Billions more still have

flown into the state over the past two years in the form of

federal coronavirus funds, more than $2 billion of which

remain unspent.

“Massachusetts has money coming in, we have more than enough

to fund these critical programs that we need without raising

taxes on the hard-working families,” he said.

Opponents also pushed back on ballot question language

saying revenue generated by the tax would be earmarked for

education and transportation funding.

“The state constitution specifically prohibits earmarking

funds, revenue,” said Rep. David DeCoste, R-Norwell. “Since

the Legislature appropriates revenue, only the Legislature

will have the final word in terms of what will be spent and

for what. The idea that these funds will somehow be fenced

for transportation and education is really unrealistic.”

State House News

Service

Friday, January 14, 2022

Agreement on Tax Revenue Estimate Kicks Off Budget Cycle

By Katie Lannan

Legislative and Baker administration budget writers are

projecting that state tax revenue will grow by 2.7 percent

next fiscal year, from the $35.948 billion they are now

expecting the state to collect in fiscal 2022.

Administration and Finance Secretary Michael Heffernan and

Ways and Means Committee chairs Sen. Michael Rodrigues and

Rep. Aaron Michlewitz are required to jointly develop a

revenue forecast each year, which lawmakers and Gov. Charlie

Baker use in crafting their spending plans. Baker, who makes

the first volley in the annual budgeting process, is due to

file his bill by Jan. 26.

The trio on Friday announced a consensus revenue forecast of

$36.915 billion for the fiscal year beginning July 1, which

would make a maximum of $29.783 billion in tax revenue

available for the fiscal 2023 budget after accounting for

statutorily required transfers. In conjunction with the

announcement, Heffernan said he is revising this year's

revenue projection upward by $1.548 billion based on

year-to-date collections and economic data. As of December,

the state had collected more than $17.8 billion in taxes so

far this fiscal year.

The upgraded fiscal 2022 number assumes 5.3 percent growth

over fiscal 2021 collections, according to a Massachusetts

Taxpayers Foundation analysis, meaning the 2.7 percent

estimate for fiscal 2023 would represent a slowdown in

growth.

The fiscal 2023 estimate of $36.9 billion lands within the

range of possibilities experts offered at a December

hearing, when they said Massachusetts could expect at least

about $36.48 billion and possibly as much as nearly $40.8

billion next year, while flagging the continued uncertainty

of the pandemic and its economic toll.

"After some tumultuous budget cycles over the last several

years, this consensus revenue agreement for Fiscal Year 2023

is a reasonable and appropriate forecast that will allow the

Commonwealth to continue to provide the services our

constituents deserve, while at the same time preserving our

fiscal health," Michlewitz said. "Despite the pandemic, our

revenue intake continues to be better than anticipated,

proving the continued resiliency of the Commonwealth's

economy."

State House News

Service

Friday, January 13, 2022

Advances: Week of Jan. 16, 2022

Friday, Jan. 21, 2022

REVENUE COMMITTEE: Revenue Committee holds a virtual

hearing on 66 bills related to the environment and farms --

including bills that deal with agricultural land or climate

change adaptation -- and sales and excise taxes. The agenda

includes bills that would reduce the state's 6.25 percent

sales tax to 5 percent, and others that propose tax

exemptions for gun safes and trigger locks, zero-emission

commercial vehicles, certain medical supplies, purchases of

Energy Star-rated products and hybrid or electric cars on

Earth Day, and electric-vehicle chargers.

Lawrence Rep. F. Moran filed a bill to exempt from the sales

tax any retail sale made within 10 miles of the New

Hampshire border (H 3010). Rep. Ayers, Rep. Kearney and Sen.

O'Connor have each filed bills that would repeal the sales

tax on boats built in Massachusetts, while Sen. Barrett is

proposing to repeal the sales tax exemption for aircraft (S

1797).

A Rep. Michael Moran bill (H 3012) would allow the

Massachusetts Port Authority to tax and impose additional

regulations on transportation network companies like Uber

and Lyft.

Under a Rep. Domb bill (H 2874), a new Public Health and

Safety Fund would be seeded by an excise tax on guns and

ammunition.

A Rep. Fernandes bill (H 2894) would set up a Local

Newspaper Trust Fund and a Pre-K and After School Program

Trust Fund that would both be financed from a tax on digital

ads, like online banner ads and search engine advertising.

(Friday, 10 a.m.,

Agenda and Info)

Forbes

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

In Massachusetts, Once A Leader In Government Transparency,

Key Votes Are Hidden From The Public

By Patrick Gleason

The Washington Post published an article on January 9

critical of the Iowa Senate for a new policy that requires

reporters to now observe senate proceedings from a viewing

gallery, as is customary in most other state legislatures.

Journalists had previously been permitted on the floor of

the Iowa Senate, something unique to the Hawkeye State. Yet,

while the Washington Post deems this rule change in Iowa

worthy of national coverage, the paper hasn’t published

anything on what is arguably the least transparent state

legislative body in country: the Massachusetts statehouse.

In 1766, a decade before the Declaration of Independence was

written, the Massachusetts House of Representatives

constructed a viewing gallery, the first to do so among the

thirteen colonial legislatures, for the public to witness

debates and legislative proceedings. In his latest book,

“Power & Liberty,” historian Gordon Wood described the

creation of a public gallery in the Massachusetts statehouse

as “an important step in the democratization of American

political culture.”

Yet, whereas Massachusetts had been a historical leader in

transparency in government even prior to the nation’s

founding, today the commonwealth is arguably the least

transparent state government in the entire United States.

Two and a half centuries after being the first legislative

body to allow the public to view debates and proceedings,

today the Massachusetts Legislature is the only one in the

continental U.S. to have been closed to the public for the

entire duration of the pandemic (the Hawaii Legislature is

also closed to the public). Not far from the site of the

Boston tea party, today Bay State legislators raise taxes

behind closed doors, without so much as a recorded vote.

“There is no legislative body in America as opaque as the

Massachusetts Legislature,” says Paul Craney, spokesman for

the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, a non-partisan taxpayer

organization. “They have gotten away with passing billion

dollar budgets without a vote, passing new taxes without a

vote, making some of their votes not available to the

public.”

In addition to making laws and raising taxes in secret,

Massachusetts legislators have also refused to enacted

voter-approved citizen petitions. The abuse of authority and

concealing of the democratic process doesn’t stop there.

“Massachusetts legislators exempt themselves from the

state’s public records and open meeting laws and set their

salaries to rise at the rate of inflation, which resulted in

some part time lawmakers earning over $220,000 last year,”

adds Craney. “Until a strong minority party in the

legislature offers a contrast, and the public holds these

elected officials accountable, this type of opaque behavior

will continue to be tolerated.”

In 2009, Massachusetts legislators amended the state open

meetings law in order to centralize enforcement under the

state attorney general. Robert Ambrogi, then executive

director of the Massachusetts Newspaper Publishers

Association, said that he wasn’t even aware of the change

until after it had passed. There had been no public debate

on the matter, just as there is no public debate on many

important matters in the Massachusetts statehouse.

“A lot of the work of the Legislature takes place in

committee meetings and conference committees and all of that

happens outside the public eye,” Ambrogi added. “You want to

be able to see the deliberation and the thought process.”

One of the senior members of Massachusetts’ congressional

delegation, Congresswoman Katherine Clark (D-Mass.),

assistant speaker in the U.S. House of Representatives,

appeared NPR’s On Point on January 7 to bemoan alleged

threats to democracy and make the case for a federal

takeover of state-run elections systems that would outlaw

state voter ID laws and overturn state bans on ballot

harvesting. When asked if she has concerns about the opaque

manner in which the democratic process and legislative

business is conducted in her own state, Rep. Clark declined

to comment.

Massachusetts legislators have even gone so far as to refuse

to implement ballot measures that have been approved by

voters. In 2000, for example, Massachusetts residents voted

in favor of Question 4, a ballot measure that rolled back

the state income tax rate from 5.95% to 5.0%. Yet state

lawmakers decided to delay implementation of that tax

rollback, despite the fact that 56% of Massachusetts cast

ballots in favor.

“Instead, Beacon Hill dropped the tax rate to 5.3% and

passed a law conceding the rest — but only in small doses,

and only if the state met certain financial targets,”

explained Governing Magazine. “The first of those steps

didn’t come for another decade.”

It was only on January 1, 2020, more than two decades after

the rollback to 5% was approved by voters, that the state’s

income tax rate was finally reduced to 5.0%. In announcing

the completion of the rollback, Governor Charlie Baker (R)

said “we are finally making happen what voters called for

almost 20 years ago.”

Though the income tax cut approved by Massachusetts voters

was finally implemented by lawmakers, albeit 20 years later,

it’s not lost on many Massachusetts residents that state

lawmakers refused to carry out the will of voters so that

they could tax more of their income. "And to think about the

billions of dollars that the state government has siphoned

from taxpayers' wallets during all those years," said

Chip Ford, executive director of Citizens for Limited

Taxation, the organization that led the campaign in

favor of Question 4 back in 2000. "It's disgraceful."

The Washington Post reported that the decision in the Iowa

Senate to move journalists to a viewing gallery “raised

concerns among free press and freedom of information

advocates who said it is a blow to transparency and open

government that makes it harder for the public to

understand, let alone scrutinize, elected officials.” Yet,

unlike in the Massachusetts Legislature, the public is at

least allowed into the Iowa Legislature and can view state

legislative business in person. If the Washington Post and

other national outlets are looking for a statehouse that is

lacking in government transparency, they would do well to

turn their attention to the golden dome on Boston’s Beacon

Hill.

The Courier Journal

(Louisville, KY)

Friday, January 14, 2022

Property taxes on Kentuckians' cars and trucks are jumping.

Here's why and what you can do

By Matthew Glowicki

Kentuckians could see property taxes on their cars and

trucks leap this year when renewing their vehicle

registrations.

Like with many rising prices these days, COVID is to blame.

Supply shortages caused by the pandemic have made new

vehicles scarce, pushing buyers to previously owned options,

which in turn has increased used car values.

In Kentucky, where property tax is assessed each year on the

value of motor vehicles, this spells a likely uptick in what

people will owe.

For instance, Wayne County resident Randy Bauer was told by

local officials that his 2019 Toyota 4Runner, which he

bought in late 2018 for about $38,000, has a 2022 valuation

of around $42,000.

“I’ve never had vehicles appreciate, especially when they

appreciate over what you’ve paid for them brand new,” Bauer

told Reader’s Watchdog, adding he’ll owe just under $500 in

taxes.

Car values, overall, are jumping about 40% this year

compared to last year, according to a letter sent by the

Kentucky Department of Revenue to county officials.

The state updates these trade-in values yearly through its

vendor, market research firm J.D. Power.

In the letter, the revenue department cites well-documented

recent trends in the automobile industry, including new

vehicle production constraints — due to computer chip

shortages, for one — increased new vehicle prices and

limited used car supply, as factors contributing to the jump

in used car prices.

Bauer, who moved to Kentucky last year, said it seemed

unfair to him to be taxed on an inflated value of his

vehicle.

“They ought to be able to leave it the way it is and not

raise it,” Bauer said.

Kentucky legislature eyes car taxes

In response to the likely tax increase, as of Jan. 12,

Kentucky legislators had filed at least four bills

addressing vehicle property taxes.

House Bill 6 would require the state to use the “average”

trade-in value instead of the “clean” trade-in value when

assessing a vehicle’s valuation, thereby lowering the

taxable amount. It also would allow those who already paid

their 2022 vehicle property tax using the current method to

seek a refund.

House Bill 261 and Senate Bill 75 propose using prior-year

values when assessing values in 2022 and 2023.

"We have people who are dealing with a higher cost of living

because of all the impacts of the coronavirus,” Sen. Jimmy

Higdon, R-Lebanon, said in a news release about his bill, SB

75. “They don't deserve to have to pay more on this tax

because of a situation out of their control."

HB 261 further proposes limiting future taxes, starting in

2024, by only taking into account up to a 6% rise in

assessed value for taxation purposes, even if that

percentage is actually higher.

Similarly, Senate Bill 70 would limit taxes on appreciating

vehicles by only taking into account up to a 5% rise in

assessed value for taxation purposes.

Auto values can be appealed to the PVA

Colleen Younger, Jefferson County's property valuation

administrator, said she didn’t have data on how much more

the average vehicle owner stood to pay, but she offered an

example of one of the most in-demand vehicles.

In 2020, a 2019 Toyota Corolla was valued at $13,450. Last

year, it dropped to $12,900 but this year skyrocketed 48% to

$19,050.

Based on a Jefferson County average of $13.50 in taxes per

$1,000 of value, that means the tax on the Corolla last year

would have been $174 compared to $257 in 2022.

Younger said she welcomes legislative action to help

taxpayers, as under state law, motor vehicles must be

assessed and taxed yearly.

“I think any time you have an erratic market, whether in

motor vehicle or real property, there should be some type of

circuit breaker solution to dealing with the erratic market

and how it stands to hurt taxpayers,” she said.

State law allows for appeals to the PVA, within 60 days of

receiving the notice of renewal. Such notices are typically

sent the month before renewal is due, which is the owner’s

birth month, according to the Department of Revenue.

Younger encouraged vehicle owners to appeal if they have

vehicle damage that would lessen its value or if they drive

more than 10,000 miles a year, as standard valuations are

based off that marker.

“But it’s up to the automobile owner to substantiate any

kind of high mileage, damage or mechanical defect," she

said.

Her office is readying a campaign to alert vehicle owners

that they can appeal their valuation. Individuals can appeal

by bringing supporting documentation to their local PVA

office. Younger said there are plans to roll out a service

for Jefferson County citizens to appeal online in the coming

weeks.

Jefferson County residents can contact the PVA office at

502-574-6450. A list of PVA offices statewide can be found

at jeffersonpva.ky.gov/community-links/kentucky-pva-offices/.

Bauer said he was pleased to hear vehicle valuations are

able to be appealed and heartened that state legislators may

address the issue, though he plans on paying the tax as

billed. |

NOTE: In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this

material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior

interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes

only. For more information go to:

http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

Citizens for Limited Taxation ▪

PO Box 1147 ▪ Marblehead, MA 01945

▪ (781) 639-9709

BACK TO CLT

HOMEPAGE

|