|

“Every Tax is a Pay Cut ... A Tax Cut is a Pay Raise”

48 years as “The Voice of Massachusetts Taxpayers”

— and

their Institutional Memory — |

|

|

After nearly half a

century of saving Massachusetts taxpayers countless billions of

their dollars,

Citizens for Limited Taxation will be permanently shut down on December

31, 2022

due to insufficient and diminishing support from those taxpayers.

Goodbye, and good luck. |

CLT UPDATE

Saturday, December 31, 2022

Reactions to CLT's

Imminent Shutdown:

Is Taking Out Proposition 2½ the First Target?

Jump directly

to CLT's Commentary on the News

|

Most Relevant News

Excerpts

(Full news reports follow Commentary)

|

|

More than

900,000 Massachusetts residents have received tax

refunds so far under Chapter 62F [CLT's 1986 Tax Cap

law], the controversial tax cap law that’s requiring

state government to return nearly $3 billion in

excess revenues back to taxpayers.

That

equates to nearly $1 billion distributed to eligible

Bay Staters as of Tuesday, a state official told

MassLive Thursday evening.

The Baker

administration began doling out checks at the start

of November, with the distribution process expected

to span through mid-December. It’s a randomized

rollout, meaning officials are not sending refunds

to the lowest earners first, alphabetically, or in

any other predictable order....

The

Department of Revenue previously said it intended to

send out about 500,000 Chapter 62F refunds in the

first week, followed by about 1 million in

subsequent weeks “until all currently eligible

refunds have been distributed.”

The

Springfield Republican

Friday, November 11, 2022

At least roughly $1 billion

in tax refunds sent to Mass. residents so far

Lower the

flag to half-staff. Don a black armband. Citizens

for Limited Taxation — one of the most admirable

grass-roots organizations ever created in

Massachusetts and the most influential ally the

commonwealth’s taxpayers ever had — has passed away

peacefully at 48.

In

a final

e-mailed update to supporters and friends on

Nov. 11, CLT’s executive director Chip Ford reviewed

the results of the election, analyzed developments

on Beacon Hill, and expressed gratitude to the small

band of donors who kept CLT alive for so many years.

He noted with pride that CLT had saved Massachusetts

taxpayers “tens of billions of their dollars” and

was “leaving them in a far better place than had CLT

never existed.”

The most

recent evidence of CLT’s beneficent legacy is —

literally — in the mail. Even as the organization

turns out its lights for the last time, checks are

being mailed this month to every single Bay State

taxpayer under the terms of a 1986 law limiting

state tax revenue from growing faster than the wages

and salaries of Massachusetts residents. It was CLT

that drafted that law and got it on the ballot in

the teeth of

opposition from Beacon Hill. Because CLT refused

to stand down then, $3 billion is on its way back to

taxpayers now....

Again and

again, CLT saddled up to fight for tax relief. A

long crusade to roll back the income tax rate in

Massachusetts to 5 percent

finally prevailed in 2000. CLT repeatedly had to

head off attempts by legislators to eviscerate

Proposition 2½ and always found itself ridiculously

outmatched, above all when it came to staff and

money. At its peak, it had only four paid staffers —

and they were paid a pittance. Before she retired as

executive director, Anderson was getting just $10 an

hour. For CLT’s devoted activists, it was never

about their money. It was always about the people’s

money. In the Commonwealth’s storied history,

perhaps no one since Samuel Adams has done more for

the sake of Massachusetts taxpayers.

Over time,

Massachusetts taxpayers came to take CLT for

granted. They got used to property taxes that could

no longer shoot upward, to auto excise fees that

were modest, and to an income tax lower than that in

many other states. Having achieved most of what it

set out to accomplish, CLT saw its thousands of

supporters dwindle to just a few dozen. Its funding,

always modest, trickled to a halt.

Anderson died of cancer in 2016; Ford, now 73,

is retiring.

For nearly

half a century, Citizens for Limited Taxation fought

the good fight with hard work, fierce integrity, and

good humor, leaving Massachusetts better than it

found it. If you live in this state, CLT deserves

your thanks.

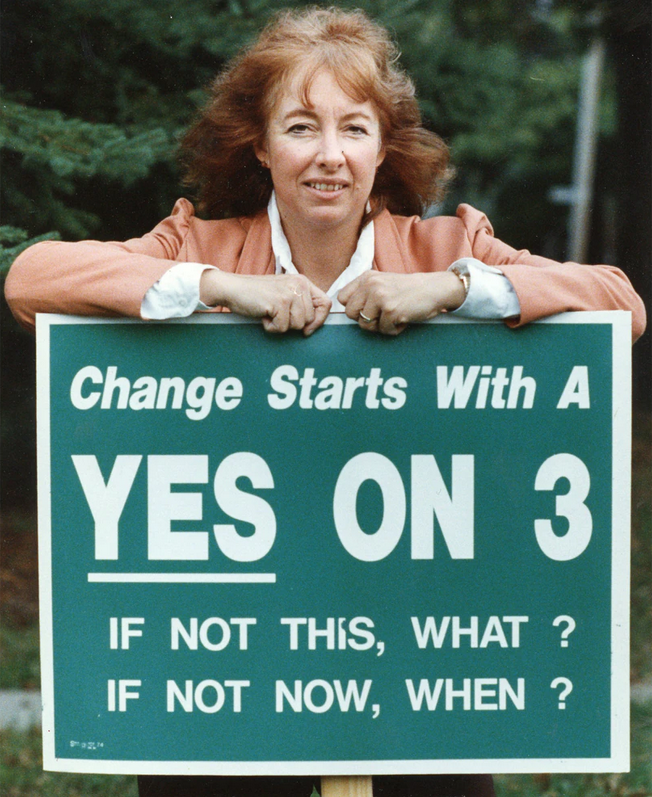

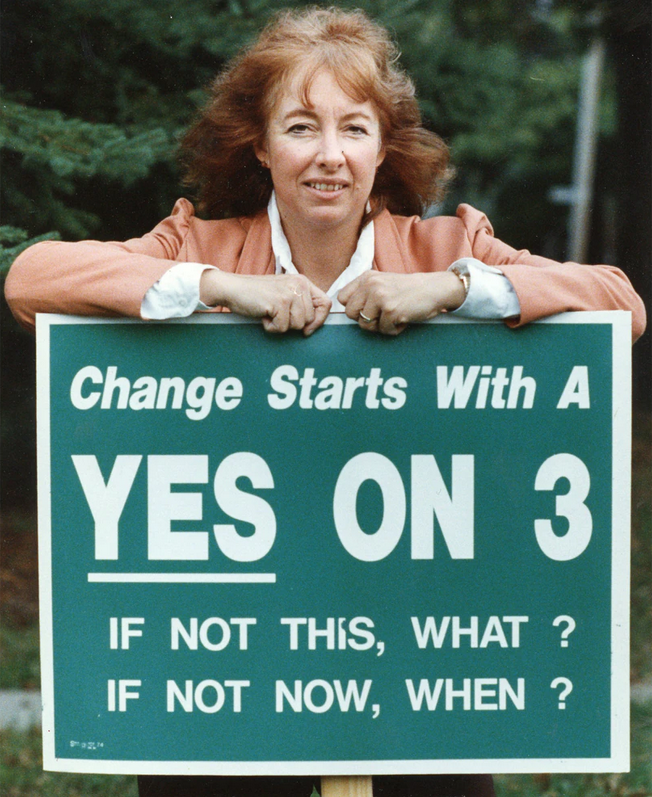

Barbara

Anderson, the longtime executive director of

Citizens for Limited Taxation,

outside of her home in Marblehead, Mass., in 1990.

The

Boston Globe

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

RIP, Citizens for Limited Taxation

The most influential ally Massachusetts taxpayers

ever had is turning out the lights.

By Jeff Jacoby

Citizens

for Limited Taxation, one of the most powerful

forces on Beacon Hill for nearly a half century, one

that has kept billions of dollars in your wallet and

away from the government, has quietly closed its

doors.

R.I.P.,

CLT.

Have you

gotten a check or a deposit from the state lately?

In fact, more than 1.3 million Massachusetts

taxpayers have received about $1.2 billion in

refunds, and there are still 1.8 million people

awaiting another $1.8 billion.

Thank CLT.

Back in

1986, the small band of taxpayer advocates backed a

referendum preventing state tax revenue from growing

faster than the salaries and wages of Massachusetts

residents. Beacon Hill objected, of course, but

voters approved the proposal.

For years,

the law was forgotten. But the law resurfaced this

year when Massachusetts enjoyed a historic surplus

and the state was forced to return about $3 billion

to taxpayers.

Because

CLT fought state leadership, you received or will

get a refund that will at least take a little sting

out of the skyrocketing prices of food and fuel.

But CLT is

best known for the law known as Proposition 2½....

CLT was

always a small group without a lot of money.

Anderson’s top pay as executive director reportedly

was $10 an hour.

The ranks

have grown even thinner in recent years, as has the

money.

Anderson

died of cancer in 2016, followed three years later

by Faulkner, also of cancer.

The

current executive director, Chip Ford, is retiring

at age 73. In a final email sent to supporters and

friends, he thanked the donors who kept the

organization alive for 48 years. The organization,

Ford said, saved Massachusetts taxpayers “tens of

billions of dollars” and was “leaving them in a far

better placed than had CLT never existed.”

That’s

very true, and that’s why I’ll say it again — and

why we should all say it.

Thanks,

and R.I.P., CLT.

The

[Attleboro] Sun Chronicle

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Thank you CLT

By Mike Kirby

It’s the

day after the midterms and one of the biggest issues

on the ballot — Question 1 about income tax rates —

has either won or lost.

The

referendum was widely endorsed, including by The Sun

Chronicle, but it was not necessarily on its way to

victory as I sat down last week to write this

day-after column.

That is

the local connection to previous statewide anti-tax

campaigns which go all the way back to 1980 and —

does this ring a bell? — Proposition 2½.

The local

connection is Francis “Chip” Faulkner, a Norfolk

native, president of the Class of 1963 at King

Philip Regional High School, longtime resident of

Wrentham (and later Attleboro). He was well known to

conservative politicians and his memory was honored

in 2020 by placement of a bench and plaque in the

lobby of KPRHS.

Faulkner

was the No. 2 person in Citizens for Limited

Taxation which was led by tax foe Barbara Anderson

for 35 years. She was a media personality and an

indefatigable campaigner against a graduated income

tax, but she also could make people laugh.

She told

The Boston Globe in 1994, “There are three reasons

to oppose the grad tax: One, you can’t trust the

Legislature; two, it’s bad for the economy; and

three, you can’t trust the Legislature.”

Anderson

died in 2016 and Faulkner in 2019, but their legacy

lives on....

Proposition 2½ was only one of CLT’s undertakings.

[Faulkner] and Barbara Anderson were drivers of

successful efforts to repeal a state income tax

surtax and defeat a “temporary” state income tax

rollback which was not what it seemed.

As for the

1994 campaign against a graduated income tax they

had the support of Republican Gov. William Weld, who

skewered the proposal with a famous one-liner: “I

majored in classics and I think I know a Trojan

horse when I see one.”

Weld won

re-election that year with 71 percent of the vote

while the grad tax proposal lost by almost as much,

69.6 percent.

The

current governor, Republican Charlie Baker, was a

Weld protégé and served in his administration. Baker

did not take a firm stand on Question 1, saying

only, “I don’t think we should be raising taxes.”

But in eulogizing Barbara Anderson in 2016, he

credited her with moving Massachusetts from the

sixth-heaviest taxed state to 36th.

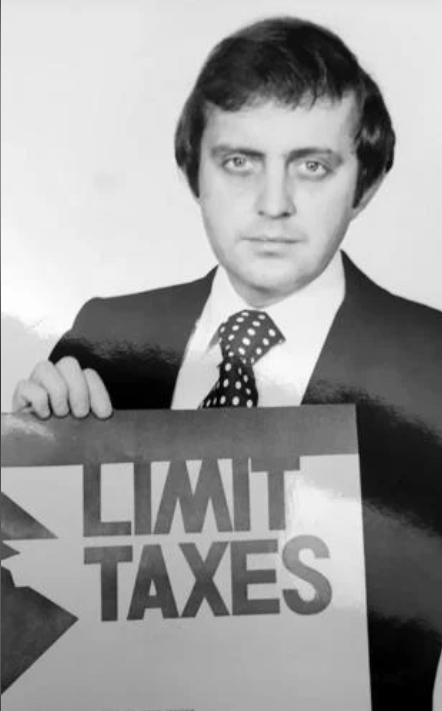

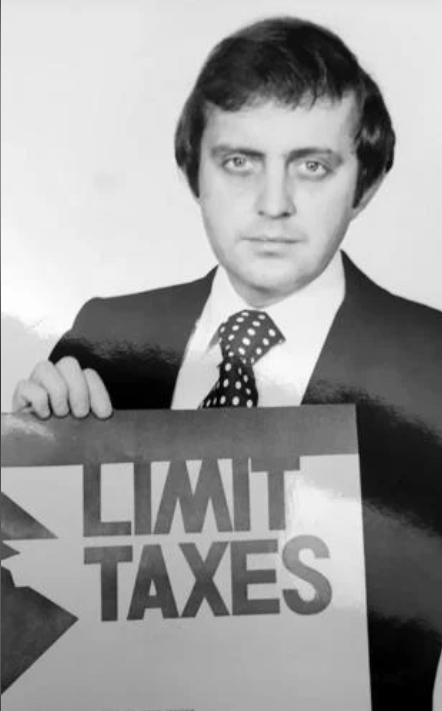

Chip

Faulkner, shown in 1978, was an advocate for the

tax-limiting law

that eventually became known as Proposition 2½.

Sun Chronicle ARCHIVES

The

Attleboro Sun Chronicle

Wednesday, November 9, 2022

What would Chip Faulkner

think?

By Ned Bristol

Was it

greed or envy or resentment? Or was it all three

that prompted just over half the state to vote for

the Question 1 tax hike on Nov. 8?

It

couldn’t have been want of money. Even as the voting

took place, Massachusetts taxpayers were/are getting

tax refunds. Those refunds are coming, courtesy of

Citizens for Limited Taxation, because Massachusetts

had a tax surplus in 2021, and, according to the

law, overtaxed its citizens.

In

addition to that, the state is awash in money: This

year’s tax receipts are running 5% ahead of last

year, which ran 20% ahead of the year before, which

ran 15% ahead of the year before that.

Voters

knew all this, so something besides a need for money

motivated the “yes” vote. Despite the advocates

outspending the opposition 2:1, the vote was a close

52-48. The proponents claimed it was just a

“millionaire” tax – implying that only those

routinely earning ordinary income of over $1 million

would pay. But that’s not true. The surtax also

applies to sales of small businesses and homes.

I know of

a woman who enthusiastically voted for the tax hike.

She thought it applied only to those with annual

income over $1 million. Then she found out that the

million-dollar threshold also applies to the money

she’ll get when she sells one of her two houses. She

was horrified and utterly distraught.

Apparently, life was joyous when she voted to take

away other people’s money. (They have too much

anyway.) But her money, well now, that’s a different

matter entirely.

The woman

is not exceptional. We all know people of similar

bent....

There is,

of course, another category of takers: those who are

always feeding at the government trough. For them,

the tax take is never large enough, and they find it

easy to vote other people’s money for themselves.

The action

of these constituencies was manifest in places that

are hotbeds of left-wing sentiment. Boston approved

the surtax with 65%. Cambridge delivered 75%

approval; Somerville, 79%.

In this

matter, Massachusetts lurched further left than even

ultra-liberal California. There, voters struck down

Proposition 30 – to impose a 1.75% tax on annual

incomes above $2 million. A bad sign when we’re to

the left of California.

Citizens

for Limited Taxation (CLT) was founded in 1975 to

oppose the fourth graduated income tax proposal –

defeated on the 1976 ballot. CLT also defeated the

fifth attempt in 1994. Now, regrettably, CLT is

closing down. But the best summary quote for the

2022 result comes from CLT’s indefatigable executive

director, Chip Ford: “I hope none of those who voted

to end the century-old flat income tax ever becomes

successful enough to regret their decision.”

Applause,

curtain.

The

Boston Herald

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Greed, envy resentment spurred

Question 1 vote

By Avi Nelson

Robert

DeNiro once said, “You’ll have time to rest when

you’re dead.” But surely the spirit of Barbara

Anderson is restless these days.

Anderson,

one of the state’s most impactful political

activists from her perch as executive director of

Citizens for Limited Taxation (CLT), passed in 2016.

Had she lived, she would be incensed about three

events this month:

● The end

of her friend and former ballot-campaign sparring

partner Jim Braude’s run as host of WGBH-TV’s

nightly news show;

● The

failure of Gov. Charlie Baker’s effort to fulfill

her dying wish for a pardon for Gerald Amirault and

his sister Cheryl, who she believed had been

unfairly convicted in a controversial 1980s child

sexual abuse case;

● And

worst of all, the official demise of CLT, the group

she steered for four decades. “The time has come to

pass the tax limitation torch on to another

generation,” said CLT Executive Director Chip Ford,

who’s been keeping the group alive on a shoestring

since decamping to Kentucky four years ago....

Ford says

he hopes the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance (MFA), a

conservative non-profit that’s been turning out

polls, lawsuits and literature attacking the

tax-and-spend establishment for a decade, can fill

the breach. He says he’s impressed with their

“organizational ability” and “high-tech capacity.”

But he

also says MFA lacks “institutional memory” and

doesn’t “grasp the magnitude of a petition drive,”

CLT’s signature technique for harnessing populist

anti-tax backlash. That’s an understatement....

CLT was a

legit grassroots operation – at its peak, a few

business contributors and a bunch of small-dollar

donors gave them a puny $250,000 budget to work

with. A 2020 MFA federal tax filing reports $490,532

in contributions and grants, apparently not enough

to buy a fraction of the visibility and clout

Anderson once wielded....

“I think

Massachusetts is a hopeless cause,” says Ford.

That’s bad news for Barbara Anderson’s legacy, not

to mention all others who pale at the prospect of

future tax hikes. As Cheri Reval, author of “Haunted

Massachusetts,” once put it: “If the dead can’t rest

in peace, how on Earth can the living?”

MASSterList

Monday, December 26, 2022

Keller @ Large

Why Barbara Anderson can’t

rest in peace

Over the

last few decades, Massachusetts has passed a host of

major laws and regulations that made good sense at

the time but aren't well-suited for our current,

overheated economic environment. Recall the recent

kerfuffle over state tax rebates and 62F, and then

imagine it splintered across the policy landscape as

other long-standing laws have their unforeseen

quirks exposed by a new economic reality.

Take

Proposition 2½, a 1980s-era ballot initiative

setting strict limits on property taxes in cities

and towns....

This cap

made a certain kind of anti-tax sense when inflation

was muted and real estate prices were rising at a

steady, but not extravagant, pace. In those

circumstances, it acted as a meaningful but not

debilitating check on local taxes across the 351

cities and towns in Massachusetts.

But at

moments of high inflation and tight labor markets --

like right now -- Proposition 2½ takes on a whole

different character. It doesn't just limit local tax

growth; it forces municipalities to actually cut

taxes (in real terms) even as it gets more expensive

to hire municipal workers and purchase construction

materials....

Some of

the pillars of state policy were built for a very

different economic world, one where inflation was

mild enough to be treated as background noise and

job creation was a driving challenge. But these

pillars are starting to crack; we'd be well served

to fix some and replace others.

CommonWealth Magazine

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Old laws, like Prop. 2½,

need to adapt to times

By Evan Horowitz

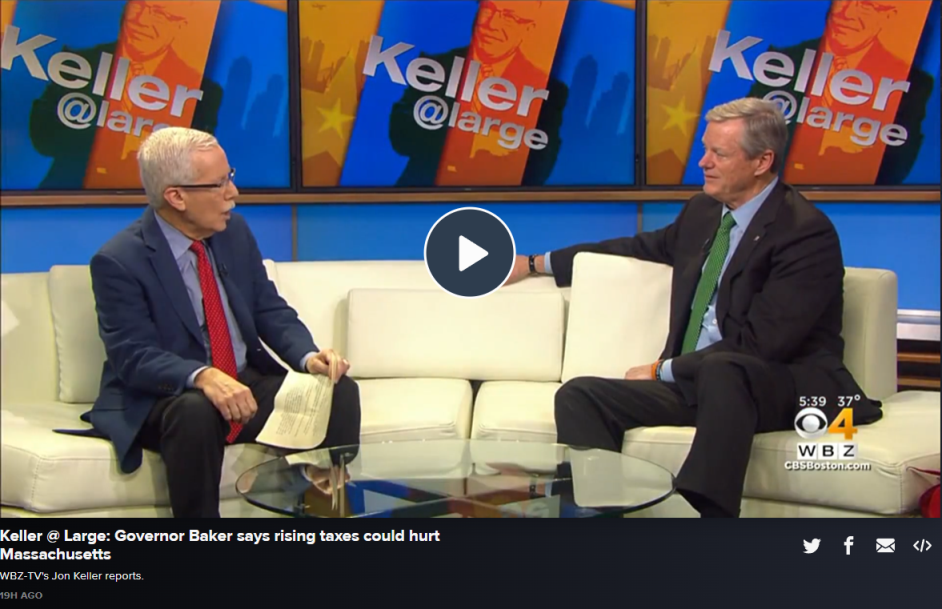

Don't

touch Proposition 2½. That's what Gov. Charlie Baker

had to say in an exit interview yesterday with WBZ's

Jon Keller. In excerpts that aired on CBS last

night, Baker talked taxes and his concern for the

message sent in November by the passage of the

so-called "millionaire's tax." "There's going to be

a lot of consequences, I think, that won't be all

that great to some of the issues associated with the

millionaires tax," Baker said.

Keller

pushed further, asking about a return to "Taxachusetts"

and whether Proposition 2½ -- the ballot law that

caps annual growth in property taxes -- could be at

risk. Baker said that during his eight years Prop 2½

was "sacrosanct," but he acknowledged that the idea

of tinkering with or scrapping the law is always

lurking just beneath the surface. "I think doing

anything to Prop 2½ would be a huge mistake," Baker

said. The full interview airs Saturday morning.

MASSterlist

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Baker: Hands off Proposition 2½

CBS

Boston | WBZ TV-4

Saturday, December 24, 2022

Keller @ Large: Governor Baker says rising taxes

could hurt Massachusetts

CLICK ABOVE GRAPHIC TO WATCH

@1:10 mins

WBZ-TV's

Jon Keller reports.

Keller:

"And what about Proposition 2½, the 41 year old

property tax limitation law that some on Beacon Hill

have been trying to undermine for years?"

Gov.

Baker: "Yes, it's always on the agenda. Prop 2½ has

been on the radar every year as long as I can

remember."

The choice

that was placed before voters on whether to levy an

additional 4% tax on high incomes raised and spent

tens of millions more dollars this general election

cycle than all of the major party statewide

campaigns for office combined....

According

to data provided by the Massachusetts Office of

Campaign and Political Finance, the campaign to

pass question 1, which passed by about 4 points,

raised over $32.2 million and spent about $28.5

million in 2022 to convince residents taxing incomes

over $1 million would result in better roads and

more successful schools.

The

general election campaigns of candidates for

governor, lieutenant governor, state treasurer,

attorney general, secretary of the commonwealth and

state auditor from the Republican and Democratic

parties raised, between the 11 of them, just $11.6

million in 2022, according to OCPF.

The

campaign against question 1 raised $14.4 million,

according to OCPF, also out-raising and outspending

all of the general election candidates.

“Tens of thousands of union members funded

this campaign with their hard-earned wages

because they cared deeply about improving our

schools, colleges, roads, and transit. And thousands

of volunteers across the state spent nights and

weekends talking to their neighbors about Question

1, because they wanted to see the ultra-rich finally

pay their fair share,” [Fair

Share Campaign spokesman Andrew] Farnitano

said....

Question

4, which asked voters whether to keep a law passed

this summer, the Work and Family Mobility Act, or to

overturn it. 53.7% of voters thought that people who

cannot demonstrate lawful presence in the state

should nevertheless be allowed driver’s licenses.

The law will take effect in July.

Supporters raised $3.6 million, opponents, who

gathered the tens of thousands of signatures

required to add the question to the ballot, raised

just $222,000.

The

Boston Herald

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Question 1 out-raised, outspent

all other statewide campaigns combined

In the

2022 midterm elections, residents of California,

like those of Massachusetts, voted to put Democrats

in commanding control of their state government.

Yet these two left-leaning electorates rendered

opposing verdicts on similar tax measures seeking to

raise state income tax rates on upper income

households.

With 57%

voting No, California voters resoundingly defeated

Proposition 30, a ballot measure that would’ve added

a new, 15.05% top marginal state income tax rate

applying to income above $2 million. At 13.3%,

California already levies the highest top personal

state income tax rate in the country....

While

Golden State voters rejected an income tax hike on

high earners, in Massachusetts another “millionaires

tax” proposal, Question One, passed with nearly 52%

support. Question One is a constitutional amendment

that will move Massachusetts from a flat to

progressive income tax structure. Massachusetts

currently has a 5% flat state income tax rate and

passage of Question One will create a new 9% rate on

income above $1 million dollars.

Question

One is projected to raise an additional $1.5 billion

annually for state coffers. Whereas the progressive

tax hike rejected by Californians would’ve been used

to fund EV infrastructure, the income tax increase

approved in Massachusetts will use the additional

funds to boost education and transportation

spending.

While

the state teachers union was a major opponent of the

defeated California income tax increase, they

were the top proponent and funder of the

Massachusetts income tax hike. The California

Teachers Association spent $5 million to defeat

Proposition 30. The Massachusetts Teachers

Association, meanwhile, spent $15.5 million in

support of Question One. The American Federation for

Teachers also kicked in $6.7 million to help pass

the income tax hike....

By moving from a flat to a progressive income tax

structure, Massachusetts is bucking a national

trend, as more states have been moving in the

opposite direction, going from a progressive to a

flat income tax. In September, Idaho became the

fifth state in the past two years where lawmakers

enacted legislation moving from a progressive to a

flat state income tax structure. Other states where

lawmakers have passed legislation to move from a

progressive to flat income tax over the past two

years include Georgia, Mississippi, Iowa, and

Arizona.

Forbes

Magazine

Wednesday, November 9, 2022

Massachusetts Voters Approve

‘Millionaires Tax’

As Californians Reject An Income Tax Hike On High

Earners

|

Chip Ford's CLT

Commentary |

|

As CLT departs the

scene in Massachusetts forever after the past 48 years of

relentlessly defending its taxpayers, it's gratifying to see

that some recognize its contribution to the commonwealth

— in terms of the actual

definition and meaning of that word.

But it wasn't just

the few who actually appreciate the multiple billions CLT

has saved Bay State taxpayers over its existence for almost

half a century. The Takers are also awakening,

sensing the potential opportunity not available for so long

to take back all that CLT has provided to The Producers.

The Takers

have noted CLT's departure and already are wheeling and

circling overhead like vultures eyeing their next carrion

banquet below. This is not surprising, considering

their longtime hatred of CLT's Proposition 2½

and its supporters, and the frustration with their failed

efforts to unwind if not destroy tax limitations of any

sort.

Moving right in, on December 11

CommonWealth Magazine published an article by Evan

Horowitz, the executive director of the Center for

State Policy Analysis at Tufts University,

presenting the most direct assault on Proposition 2½

in memory ("Old laws, like Prop. 2½, need to adapt to times").

I expect their gloves are off and they'll be coming

for Prop

2½ very soon. Here's a

few excerpts of what Horowitz asserted:

Over the last few decades,

Massachusetts has passed a host of major laws and

regulations that made good sense at the time but aren't

well-suited for our current, overheated economic

environment. Recall the recent kerfuffle over state tax

rebates and 62F, and then imagine it splintered across

the policy landscape as other long-standing laws have

their unforeseen quirks exposed by a new economic

reality.

Take Proposition 2½, a 1980s-era

ballot initiative setting strict limits on property

taxes in cities and towns....

This cap made a certain kind of

anti-tax sense when inflation was muted and real estate

prices were rising at a steady, but not extravagant,

pace. In those circumstances, it acted as a meaningful

but not debilitating check on local taxes across the 351

cities and towns in Massachusetts.

But at moments of high inflation

and tight labor markets -- like right now -- Proposition

2½ takes on a whole different character. It doesn't just

limit local tax growth; it forces municipalities to

actually cut taxes (in real terms) even as it gets more

expensive to hire municipal workers and purchase

construction materials....

Some of the pillars of state policy

were built for a very different economic world, one

where inflation was mild enough to be treated as

background noise and job creation was a driving

challenge. But these pillars are starting to crack; we'd

be well served to fix some and replace others.

Horowitz hopes his

audience is too ignorant to recall events that happened more

than twenty minutes ago, let alone what was happening 43

years ago in 1980 when our Proposition 2½

ballot question was adopted by an overwhelming vote of

60%-40%. We CLT members and staff are not. We

are aware that Prop 2½ passed

the same year Ronald Reagan was first elected president

after trouncing the last Democrat incumbent, Jimmy Carter,

who delivered the worst inflation in memory, even worse than

today's Bidenflation.

"But at moments of high inflation and

tight labor markets — like right now — Proposition 2½ takes

on a whole different character," Horowitz,

the executive director of the Center for State

Policy Analysis at Tufts University, pronounced. "Some

of the pillars of state policy were built for a very

different economic world, one where inflation was mild

enough to be treated as background noise and job creation

was a driving challenge. But these pillars are starting to

crack; we'd be well served to fix some and replace others,"

he added.

But that is either an intentional lie or his

ignorance alone should disqualify him for his position with

Tufts University.

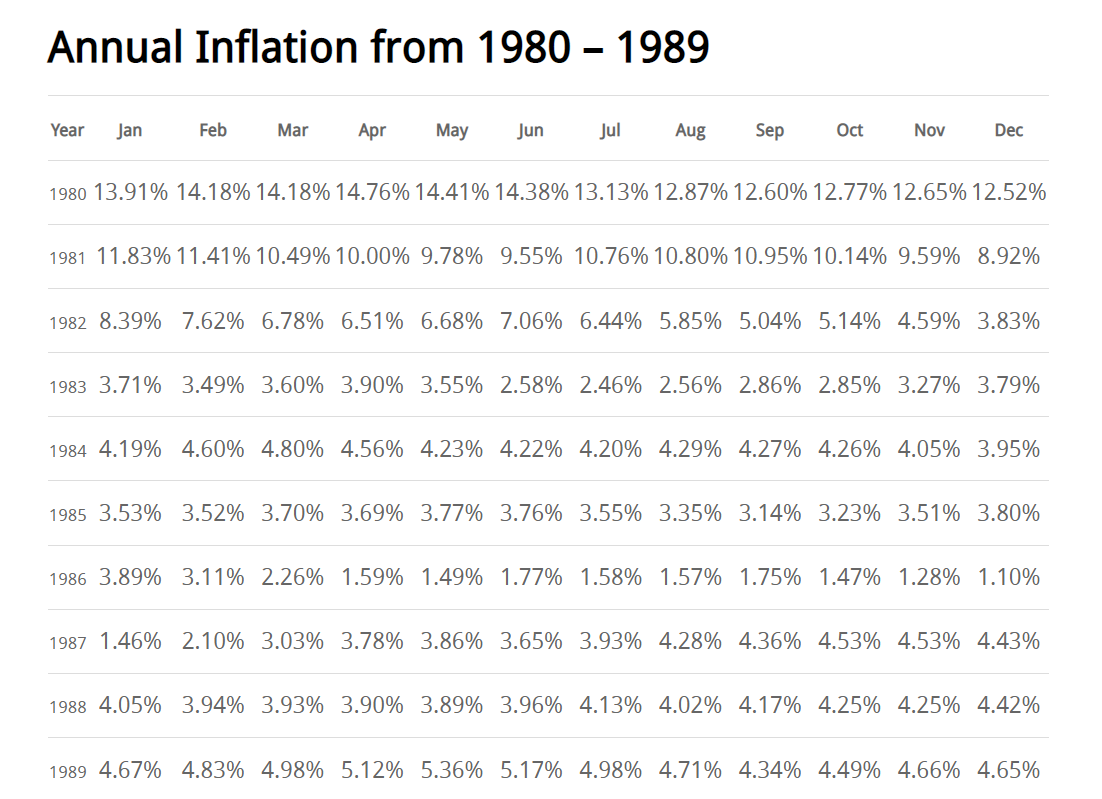

According to

InflationData.com ("Inflation

in the 1980s"):

In January 1980, Inflation was

13.91%, and Unemployment was 6.3%. Inflation peaked in

April 1980 at 14.76% and fell to “only” 6.51% the

following April. By December 1989, Inflation had

decreased drastically to 4.65%, and Unemployment had

declined to 5.4%.

U.S. inflation on

election day 1980 — when CLT's

Proposition 2½ was vigorously adopted

— stood at 12.65%.

The U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics announced this week that current inflation

rate for last month came in at 6.5%.

The unemployment

rate for last month was 3.5% — just

over half the 6.3% rate of 1980.

Nice try Evan but you've just been

exposed as another deceptive tool of The Takers.

On Friday the entire staff at

MassFiscal and I engaged in a Zoom conference meeting to

discuss Proposition 2½ so I could enlighten them

further on its many subtleties, the little-known or

understood complexities, and how they all work together as a

unified package to limit municipal taxation. (You can

read

my briefing paper here.) Going forward I expect

they will be up to the job of preserving and protecting

Proposition 2½.

If you too want to see that happen,

then I recommend that you quickly

contact and support the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance

and join their team. Lack of actual support killed

CLT. Now you know that it can, and did happen. I

hope you won't let that happen to MassFiscal, or truly you

will be entirely on your own.

In early June of

last year I recognized the waning interest and support of

taxpayers for Citizens for Limited Taxation. We had

been here before, in 2018, and the result was CLT needing to

shut down before the funds entirely ran out. The

situation in 2022 had only become even graver.

Soon after members

had

the letter from CLT in their hands announcing the

decision to shut down CLT permanently we were all blindsided

by the fantastic news on July 27 that CLT's 1986 Tax Cap law

had been triggered (for only the second time) and a large

refund to taxpayers was likely due to them. So much

for CLT quietly fading away as my days became more

leisurely. Suddenly it was full battle mode around the

clock through mid-December to ensure the refunds went out as

mandated by our law.

If I hadn't

decided in June that CLT required to be shut down due to the

obvious lack of support this would have guaranteed it.

For a long time I've recognized that Citizens for Limited

Taxation is the only organization, the only entity I've ever

heard of where the more successful it was, the more of their

money it saved taxpayers, the more it was punished by them

with less and less support. Providing a $3 Billion

refund in one lump sum to 3.4 million taxpayers would have

drove the final nail into CLT's coffin. The punishment

would have crushed what little of CLT remained. We

dodged that retribution just by the skin of our teeth with

that already-planned exodus!

A few days before

her death Barbara and I had a very solemn discussion about

CLT's future, whether I would keep it going and what would

happen to Proposition 2½ without CLT

there to defend it. She was highly concerned about

seniors living on fixed incomes being forced out of their

homes if property tax policies returned to where they were

prior to 1980. I told her I'd keep CLT going "for as

long as humanly possible" and I did that for the next six

years. My primary focus since making that promise to

her has been defending Proposition 2½.

Now it is out of my hands and back in yours — and those of

the MassFiscal staff. I pray that will be enough to

keep it alive for decades to come.

I wish you the best of luck and

success with that in the months and years ahead. I'll

be watching from afar, rooting for you.

|

|

|

|

Chip Ford

Executive Director,

Retired |

|

|

|

The

Springfield Republican

Friday, November 11, 2022

At least roughly $1 billion in tax refunds sent to Mass.

residents so far

By Alison Kuznitz

More than 900,000 Massachusetts residents have received tax

refunds so far under Chapter 62F, the controversial tax cap

law that’s requiring state government to return nearly $3

billion in excess revenues back to taxpayers.

That equates to nearly $1 billion distributed to eligible

Bay Staters as of Tuesday, a state official told MassLive

Thursday evening.

The Baker administration began doling out checks at the

start of November, with the distribution process expected to

span through mid-December. It’s a randomized rollout,

meaning officials are not sending refunds to the lowest

earners first, alphabetically, or in any other predictable

order.

Refunds, which are being sent as paper checks in the mail

and via direct deposits, equal about 14% of an individual’s

2021 personal income tax liability. No action is needed from

eligible Bay Staters — namely, those who filed their tax

returns by mid-October or who will do so by mid-September —

to receive the refunds, according to updated eligibility

parameters.

About 200,000 refunds were distributed via direct deposit so

far, with another 700,000 refunds as issued as checks in the

mail, the state official told MassLive.

The Department of Revenue previously said it intended to

send out about 500,000 Chapter 62F refunds in the first

week, followed by about 1 million in subsequent weeks “until

all currently eligible refunds have been distributed.” But

officials warned delays in the U.S. Postal Service might

slow down the process.

Bay Staters can direct their questions about Chapter 62F

refunds to a state call center at 877-677-9727. It’s

available from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. on weekdays.

The call center has fielded more than 5,600 calls so far,

answering questions about refund amounts and Chapter 62F

overall, the state official said.

The Boston

Globe

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

RIP, Citizens for Limited Taxation

The most influential ally Massachusetts taxpayers ever

had is turning out the lights.

By Jeff Jacoby

Barbara

Anderson, the longtime executive director of

Citizens for Limited Taxation,

outside of her home in Marblehead, Mass., in 1990.

Lower the flag to half-staff.

Don a black armband. Citizens for Limited Taxation — one of

the most admirable grass-roots organizations ever created in

Massachusetts and the most influential ally the

commonwealth’s taxpayers ever had — has passed away

peacefully at 48.

In a final e-mailed

update to supporters and friends on Nov. 11, CLT’s

executive director Chip Ford reviewed the results of the

election, analyzed developments on Beacon Hill, and

expressed gratitude to the small band of donors who kept CLT

alive for so many years. He noted with pride that CLT had

saved Massachusetts taxpayers “tens of billions of their

dollars” and was “leaving them in a far better place than

had CLT never existed.”

The most recent evidence of CLT’s beneficent legacy is —

literally — in the mail. Even as the organization turns out

its lights for the last time, checks are being mailed this

month to every single Bay State taxpayer under the terms of

a 1986 law limiting state tax revenue from growing faster

than the wages and salaries of Massachusetts residents. It

was CLT that drafted that law and got it on the ballot in

the teeth of opposition

from Beacon Hill. Because CLT refused to stand down

then, $3 billion is on its way back to taxpayers now.

I first heard of Citizens for Limited Taxation in 1980. I

was a newcomer to the state and CLT was the moving force

behind an earlier ballot initiative: Proposition 2½. In

those days, residents of “Taxachusetts” staggered under one

of the highest tax burdens in the nation. But they could get

no relief from Beacon Hill, which was a wholly owned

subsidiary of the Democratic Party and the public-employee

unions.

That didn’t deter CLT, a small but committed band of

activists led by an intrepid free spirit named Barbara

Anderson. (Ford became Anderson’s codirector in 1996). In

the face of wall-to-wall hostility from the state’s

political class, CLT urged voters to approve Proposition 2½,

which was designed to cut property and auto excise taxes,

and establish an income-tax deduction for renters.

Opponents warned that if Proposition 2½ passed, the results

would be catastrophic. Buildings would burn to the ground

for lack of firefighters, sick people would die for lack of

hospitals, and children would wallow in ignorance for lack

of schools. The Massachusetts League of Cities and Towns

prophesied that a yes vote “would effectively wipe out

government.” The Boston Globe urged its readers to vote no,

condemning Proposition 2½ for its “meat-ax approach” and

scorning its supporters as “fanatical.”

The voters trusted CLT. Proposition 2½ became law. Far from

unleashing a cataclysm, the law became —

as the Globe would eventually acknowledge — “the most

powerful engine of change in recent Massachusetts political

history” and the foremost factor in “the state’s amazing

turnaround.”

CLT first came into existence in 1974. It was launched to

fight a proposal to replace the state’s flat-rate income tax

with graduated tax brackets, a proposal it defeated in the

1976 election. In 1994, when a grad-tax proposal was again

on the ballot, CLT again beat it back.

Again and again, CLT saddled up to fight for tax relief. A

long crusade to roll back the income tax rate in

Massachusetts to 5 percent

finally prevailed in 2000. CLT repeatedly had to head

off attempts by legislators to eviscerate Proposition 2½ and

always found itself ridiculously outmatched, above all when

it came to staff and money. At its peak, it had only four

paid staffers — and they were paid a pittance. Before she

retired as executive director, Anderson was getting just $10

an hour. For CLT’s devoted activists, it was never about

their money. It was always about the people’s money. In the

Commonwealth’s storied history, perhaps no one since Samuel

Adams has done more for the sake of Massachusetts taxpayers.

Over time, Massachusetts taxpayers came to take CLT for

granted. They got used to property taxes that could no

longer shoot upward, to auto excise fees that were modest,

and to an income tax lower than that in many other states.

Having achieved most of what it set out to accomplish, CLT

saw its thousands of supporters dwindle to just a few dozen.

Its funding, always modest, trickled to a halt.

Anderson died of cancer in 2016; Ford, now 73, is

retiring.

For nearly half a century, Citizens for Limited Taxation

fought the good fight with hard work, fierce integrity, and

good humor, leaving Massachusetts better than it found it.

If you live in this state, CLT deserves your thanks.

The New York

Times

December 8, 1985

Lobbying Group Seeks Tax Repeal

Special to the New York Times

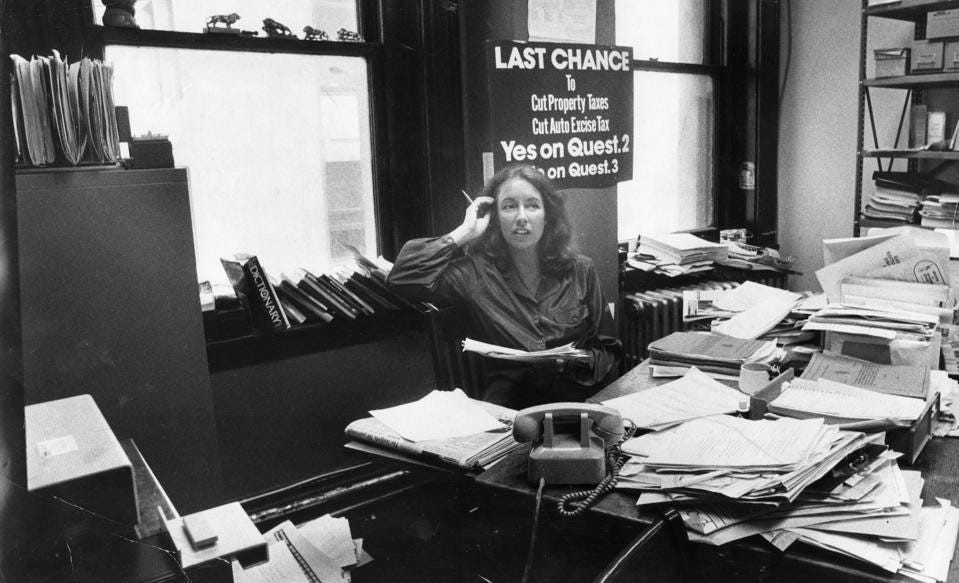

Visitors to the downtown offices of Citizens for Limited

Taxation catch on very quickly that this organization

emphasizes substance, not style.

Entry is by way of an elevator tucked into the dining area

of a fast-food restaurant. Passage to the top is shared with

mops and buckets of floor cleaner.

Once inside, visitors are greeted by partly consumed meals,

half-empty coffee cups and reams of computer printouts.

But mention Citizens for Limited Taxation or its leader,

Barbara Anderson, to a state legislator, and he will likely

snap to attention - albeit sometimes grudgingly.

In five years this band of tax-curb advocates has become one

of the most effective and controversial political forces in

the state. Its members forced the tax-limiting Proposition

2½ on state government in 1980, with the support of 60

percent of the electorate and against the opposition of most

appointed and elected officials. The law caps municipal

taxing authority at 2½ percent of the fair market value of

property.

Starting at Grass Roots

''Everything starts at the grass roots level,'' Mrs.

Anderson says. ''None of the important issues start at the

government level.''

This week, her organization wrote what is widely regarded as

the second chapter of this state's tax revolution. It

collected more than 135,000 signatures in support of a

petition to repeal the state's 7.5 percent surtax on

personal income. The tax was imposed in 1975 during Gov.

Michael S. Dukakis's first term. The number of signatures is

more than twice the minimum required to place the issue on

the ballot in November.

The petition also calls for limiting the growth in state tax

revenues to a three-year average of growth in taxpayers'

wages and salaries. But Mr. Dukakis and the Legislature hope

to head off that issue. They are scrambling to pass a surtax

repeal bill before the voters get a chance to vent their

feelings at the polls.

Mrs. Anderson, the leading force in this upheaval, divorced

her first husband, a military officer, after he objected to

her demonstrating against the Vietnam War. These days her

politics are generally considered conservative, but she

prefers the label populist.

She says the initiative petition is the trend of the future

and the most efficient way to return government to the

people.

Relations With Governor

Her enthusiasm for cutting taxes has given her high

visibility among the electorate and in the Statehouse, where

she is a registered lobbyist. She has access to the

Governor's policy advisers, but no access to the Governor.

Therein lies a story:

When Mrs. Anderson was introduced to Mr. Dukakis, shortly

before he regained his office in the 1982 election, she

mentioned - in jest, she says - that she hoped to repeal the

surtax. Gov. Edward J. King had tried unsuccessfully in the

bitter primary to defeat Mr. Dukakis with the surtax issue.

''The temperature in the room must have dropped 20

degrees,'' Mrs. Anderson recalled. ''He said, 'Well, you're

not going to get it' and turned on his heels.''

Since then, Mrs. Anderson says, she has not been able to get

an audience with the Governor.

Of course, the surtax repeal is no jest. It would cost the

state about $260 million a year. And with the possiblity of

a third King-Dukakis match in 1986, Mr. Dukakis would like

to see the matter resolved before the legislative year ends

Dec. 31.

Mr. Dukakis says the state can now afford to repeal the

surtax, which he signed into law in a severe recession.

Today Massachusetts is enjoying a budget surplus of historic

proportions, estimated by some to be as high as $400

million.

Opposition From Towns

The repeal effort, however, has its detractors. The

Massachusetts Municipal Association, representing

communities around the state, said last week that repeal

would leave the commonwealth's cities and towns $300 million

in the hole for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 1986.

James M. Segel, the association's executive director, said

the deficit would come from not having the surtax to offset

cuts in various Federal programs, including revenue sharing,

mass transportation assistance, housing and development

block grants.

''Why enact a permanent tax cut now?'' Mr. Segel asked.

''Why not wait until we do know the shape of the Federal

budget for fiscal year 1987?''

Mr. Segel's organization was one of the leading opponents to

Proposition 2 ½. In recent months Mr. Segel has publicly

applauded the measure and says it has helped the state

reduce its unhealthy reliance on property taxes.

Since Proposition 2½, the revenue burden on citizens has

dropped dramatically, according to a report last week by a

special tax overhaul commission. The public-private

commission said Massachusetts, for a long time derisively

regarded by industry as ''Taxachusetts,'' is now below the

national average in the per capita tax burden.

In the state Legislature, both the House and the Senate have

passed different versions of a repeal bill. Members of a

legislative conference committee, who were waiting to see

the results of the initiative petition, say they expect a

compromise to be hammered out this week.

If not, Mrs. Anderson said her organization will spend the

next 10 months embarrassing every legislator who voted

against the repeal.

The [Attleboro] Sun

Chronicle

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Thank you CLT

By Mike Kirby

Citizens for Limited Taxation, one of the most powerful

forces on Beacon Hill for nearly a half century, one that

has kept billions of dollars in your wallet and away from

the government, has quietly closed its doors.

R.I.P., CLT.

Have you gotten a check or a deposit from the state lately?

In fact, more than 1.3 million Massachusetts taxpayers have

received about $1.2 billion in refunds, and there are still

1.8 million people awaiting another $1.8 billion.

Thank CLT.

Back in 1986, the small band of taxpayer advocates backed a

referendum preventing state tax revenue from growing faster

than the salaries and wages of Massachusetts residents.

Beacon Hill objected, of course, but voters approved the

proposal.

For years, the law was forgotten. But the law resurfaced

this year when Massachusetts enjoyed a historic surplus and

the state was forced to return about $3 billion to

taxpayers.

Because CLT fought state leadership, you received or will

get a refund that will at least take a little sting out of

the skyrocketing prices of food and fuel.

But CLT is best known for the law known as Proposition 2½.

That referendum, approved in 1980, the same year

Massachusetts voters backed Ronald Reagan for president,

limits the increase in property taxes cities and towns can

collect each year to 2½ percent, plus new construction. The

law also placed a ceiling on the amount a community can

raise in property taxes, limited motor vehicle excise taxes

to 2½ percent and established an income-tax deduction for

renters.

Nearly all 351 cities and towns faced enormous budget cuts

when the law took effect, although Proposition 2½ did allow

municipalities to reduce spending in stages, by 15 percent a

year until they were under the cap.

In Attleboro, for instance, it took three years before Mayor

Gerald Keane and the city council were able to get spending

to comply with Proposition 2½. Dozens of jobs were cut, but

the city managed to find new ways to do business and to

bring in revenue.

For instance, the first trash fees and school athletic fees

were imposed at that time. Water and sewer fees, which were

largely subsidized by property taxes prior to Proposition

2½, were assessed entirely to the users.

Isn’t that just shifting the costs, you ask. Yes, but I’ll

argue that it’s better to have the people who use municipal

services pay for them than a cash-poor, house-rich widow.

Governments actually changed their ways, cutting back on

jobs and programs or simply learning to do with less.

In addition, the state began to better support municipal

governments with higher amounts of local aid. It had no

choice; the law also required the state to fund any mandates

it imposed on cities and towns.

Proposition 2½, at first vigorously opposed by Democrats and

public-employee unions, has gained widespread if begrudging

acceptance as part of the rules of the game in

Massachusetts.

What’s really amazing is that CLT had only been in existence

a few years when the referendum went before voters.

The group was formed in 1974 to fight a proposal to replace

the state’s flat income tax with a graduated system, similar

to the federal government. CLT successfully defeated that

referendum in 1976 and in 1994 when it was proposed again.

CLT was led by Barbara Anderson, a Marblehead resident with

fiery red hair and a personality to match. Often at her side

was a local man, Francis “Chip” Faulkner.

Faulkner, who lived in Wrentham before moving to Attleboro,

was hired by CLT in 1979 to work on the Proposition 2½

campaign, then stayed on in a variety of roles, including

spokesman and associate director. In my days as a reporter,

both Anderson and Faulkner were great to talk to, slinging

quotes that ticked off the political establishment.

CLT was always a small group without a lot of money.

Anderson’s top pay as executive director reportedly was $10

an hour.

The ranks have grown even thinner in recent years, as has

the money.

Anderson died of cancer in 2016, followed three years later

by Faulkner, also of cancer.

The current executive director, Chip Ford, is retiring at

age 73. In a final email sent to supporters and friends, he

thanked the donors who kept the organization alive for 48

years. The organization, Ford said, saved Massachusetts

taxpayers “tens of billions of dollars” and was “leaving

them in a far better placed than had CLT never existed.”

That’s very true, and that’s why I’ll say it again — and why

we should all say it.

Thanks, and R.I.P., CLT.

The Attleboro Sun

Chronicle

Wednesday, November 9, 2022

What would Chip Faulkner think?

By Ned Bristol

Chip

Faulkner, shown in 1978, was an advocate for the

tax-limiting law

that eventually became known as Proposition 2½.

Sun Chronicle ARCHIVES

It’s the day after the midterms

and one of the biggest issues on the ballot — Question 1

about income tax rates — has either won or lost.

The referendum was widely endorsed, including by The Sun

Chronicle, but it was not necessarily on its way to victory

as I sat down last week to write this day-after column.

That is the local connection to previous statewide anti-tax

campaigns which go all the way back to 1980 and — does this

ring a bell? — Proposition 2½.

The local connection is Francis “Chip” Faulkner, a Norfolk

native, president of the Class of 1963 at King Philip

Regional High School, longtime resident of Wrentham (and

later Attleboro). He was well known to conservative

politicians and his memory was honored in 2020 by placement

of a bench and plaque in the lobby of KPRHS.

Faulkner was the No. 2 person in Citizens for Limited

Taxation which was led by tax foe Barbara Anderson for 35

years. She was a media personality and an indefatigable

campaigner against a graduated income tax, but she also

could make people laugh.

She told The Boston Globe in 1994, “There are three reasons

to oppose the grad tax: One, you can’t trust the

Legislature; two, it’s bad for the economy; and three, you

can’t trust the Legislature.”

Anderson died in 2016 and Faulkner in 2019, but their legacy

lives on.

This year’s “millionaires tax” vote came 28 years after the

last comparable effort to amend the state Constitution to

raise taxes. Before that there were four attempts, in 1962,

1968, 1972 and 1976, all of which were landslide losses.

Question 1 was said to apply to 26,000 households, or less

than one percent of taxpayers, and the estimated proceeds of

$2 billion was ostensibly directed to education and

transportation improvements.

It’s important to note that 1980’s Proposition 2½ ballot

question was aimed at property taxes, not income taxes. It

is still in effect. It caps the amount of taxes a community

can levy on homes and businesses, but it also includes

safety valves which allow individual communities to pass

“overrides” to raise taxes.

Proposition 2½ also allows cities and towns to set different

real estate tax rates for homeowners and businesses,

something the Attleboro City Council voted to do last week.

This is the kind of nitty-gritty municipal finance that Chip

Faulkner got into. Proposition 2½ was only one of CLT’s

undertakings. He and Barbara Anderson were drivers of

successful efforts to repeal a state income tax surtax and

defeat a “temporary” state income tax rollback which was not

what it seemed.

As for the 1994 campaign against a graduated income tax they

had the support of Republican Gov. William Weld, who

skewered the proposal with a famous one-liner: “I majored in

classics and I think I know a Trojan horse when I see one.”

Weld won re-election that year with 71 percent of the vote

while the grad tax proposal lost by almost as much, 69.6

percent.

The current governor, Republican Charlie Baker, was a Weld

protégé and served in his administration. Baker did not take

a firm stand on Question 1, saying only, “I don’t think we

should be raising taxes.” But in eulogizing Barbara Anderson

in 2016, he credited her with moving Massachusetts from the

sixth-heaviest taxed state to 36th.

The vote on Question 1 says a lot about state politics and

the politicking to come for the presidential election of

2024.

— NED BRISTOL is a Sun

Chronicle columnist.

The Boston

Herald

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Greed, envy resentment spurred Question 1 vote

By Avi Nelson

Was it greed or envy or resentment? Or was it all three that

prompted just over half the state to vote for the Question 1

tax hike on Nov. 8?

It couldn’t have been want of money. Even as the voting took

place, Massachusetts taxpayers were/are getting tax refunds.

Those refunds are coming, courtesy of Citizens for Limited

Taxation, because Massachusetts had a tax surplus in 2021,

and, according to the law, overtaxed its citizens.

In addition to that, the state is awash in money: This

year’s tax receipts are running 5% ahead of last year, which

ran 20% ahead of the year before, which ran 15% ahead of the

year before that.

Voters knew all this, so something besides a need for money

motivated the “yes” vote. Despite the advocates outspending

the opposition 2:1, the vote was a close 52-48. The

proponents claimed it was just a “millionaire” tax –

implying that only those routinely earning ordinary income

of over $1 million would pay. But that’s not true. The

surtax also applies to sales of small businesses and homes.

I know of a woman who enthusiastically voted for the tax

hike. She thought it applied only to those with annual

income over $1 million. Then she found out that the

million-dollar threshold also applies to the money she’ll

get when she sells one of her two houses. She was horrified

and utterly distraught.

Apparently, life was joyous when she voted to take away

other people’s money. (They have too much anyway.) But her

money, well now, that’s a different matter entirely.

The woman is not exceptional. We all know people of similar

bent. They’re usually not middle-income working folks;

rather they’re pretty well-off themselves. But they look up

resentfully at those they perceive as better off. They

begrudge “rich” people their wealth and often harbor a

suspicion (unverified) that those riches were somewhat

ill-gotten. “Rich” is vaguely defined as anyone who has more

than they, and since we all tend to keep the other guy’s

bankbook more opulently than he does, it’s an oversized

category.

Envy, resentment, greed. Democrats and their constituencies

foster these baser instincts in promoting identity politics

and the politics of class warfare. Democrats’ 11th

Commandment: “Resent and envy thy wealthier neighbors, and

take what thou can from them.” (Democrats rank it higher

than 11th.) But remember, always expropriate by legal

process, so it’s technically not called “theft.”

Then there are those who camouflage their dislike of the

affluent with advocacy of socialism. In pure socialism there

is no private property; everything is owned by the state. So

those who profess socialism can justify seizing others’

private property without limit and without compunction. No

envy or greed here, they protest, they’re just being

devoutly socialistic.

There is, of course, another category of takers: those who

are always feeding at the government trough. For them, the

tax take is never large enough, and they find it easy to

vote other people’s money for themselves.

The action of these constituencies was manifest in places

that are hotbeds of left-wing sentiment. Boston approved the

surtax with 65%. Cambridge delivered 75% approval;

Somerville, 79%.

In this matter, Massachusetts lurched further left than even

ultra-liberal California. There, voters struck down

Proposition 30 – to impose a 1.75% tax on annual incomes

above $2 million. A bad sign when we’re to the left of

California.

Citizens for Limited Taxation (CLT) was founded in 1975 to

oppose the fourth graduated income tax proposal – defeated

on the 1976 ballot. CLT also defeated the fifth attempt in

1994. Now, regrettably, CLT is closing down. But the best

summary quote for the 2022 result comes from CLT’s

indefatigable executive director, Chip Ford: “I hope none of

those who voted to end the century-old flat income tax ever

becomes successful enough to regret their decision.”

Applause, curtain.

— Avi Nelson is a

Boston-based political analyst and talk-show host.

MASSterList

Monday, December 26, 2022

Keller @ Large

Why Barbara Anderson can’t rest in peace

by Jon Keller

Robert DeNiro once said, “You’ll have time to rest when

you’re dead.” But surely the spirit of Barbara Anderson is

restless these days.

Anderson, one of the state’s most impactful political

activists from her perch as executive director of Citizens

for Limited Taxation (CLT), passed in 2016. Had she lived,

she would be incensed about three events this month:

● The end of her friend and former ballot-campaign sparring

partner Jim Braude’s run as host of WGBH-TV’s nightly news

show;

● The failure of Gov. Charlie Baker’s effort to fulfill her

dying wish for a pardon for Gerald Amirault and his sister

Cheryl, who she believed had been unfairly convicted in a

controversial 1980s child sexual abuse case;

● And worst of all, the official demise of CLT, the group

she steered for four decades. “The time has come to pass the

tax limitation torch on to another generation,” said CLT

Executive Director Chip Ford, who’s been keeping the group

alive on a shoestring since decamping to Kentucky four years

ago.

Braude will continue to co-host his popular GBH Radio show,

but his step away from TV is the latest episode in the

long-term deterioration of the region’s once-robust

political media ecosphere.

Barbara’s advocacy for the Amiraults, sparked by evidence of

gross manipulation of the very young alleged victims by

prosecutors, was emblematic of her attraction to seemingly

hopeless causes.

And as CLT finally dissolves, it’s unclear if that torch is

being handed off to anyone capable of keeping its resistance

to pro-tax pressure from becoming yet another lost cause.

Ford says he hopes the Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance (MFA),

a conservative non-profit that’s been turning out polls,

lawsuits and literature attacking the tax-and-spend

establishment for a decade, can fill the breach. He says

he’s impressed with their “organizational ability” and

“high-tech capacity.”

But he also says MFA lacks “institutional memory” and

doesn’t “grasp the magnitude of a petition drive,” CLT’s

signature technique for harnessing populist anti-tax

backlash. That’s an understatement.

MFA filed a petition to put the gas-tax-hiking

Transportation and Climate Initiative on the ballot but

didn’t lift a finger to gather signatures. (TCI died for

lack of political support late last year.) And the meager

amount they donated to support the push for repeal of the

law allowing non-citizens to get driver’s licenses left its

proponents totally outspent down the stretch.

CLT was a legit grassroots operation – at its peak, a few

business contributors and a bunch of small-dollar donors

gave them a puny $250,000 budget to work with. A 2020 MFA

federal tax filing reports $490,532 in contributions and

grants, apparently not enough to buy a fraction of the

visibility and clout Anderson once wielded.

And while Barbara and disciples Ford and the late Chip

Faulkner wore their humble budgets and scant salaries as a

badge of honor, MFA is a less-principled animal. According

to records on file with the attorney general’s office, a

separate nonprofit that funds MFA pocketed $109,424 in

federal Paycheck Protection Program and Economic Injury

Disaster loans during the pandemic, all forgiven in full.

A nice, hypocritical windfall for a group that slammed

“radical left-wing legislators” for promoting tax hikes

while “not a single member of this progressive caucus has

forgone a paycheck or any of their other perks during the

pandemic.”

“I think Massachusetts is a hopeless cause,” says Ford.

That’s bad news for Barbara Anderson’s legacy, not to

mention all others who pale at the prospect of future tax

hikes. As Cheri Reval, author of “Haunted Massachusetts,”

once put it: “If the dead can’t rest in peace, how on Earth

can the living?”

CLICK ABOVE GRAPHIC TO LISTEN

CommonWealth Magazine

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Old laws, like Prop. 2½, need to adapt to times

Commentary by Evan Horowitz

I've been struggling to find the right metaphor for our

current economic situation. After the great recession of

2007-2009, my go-to was a staircase: the recession had

knocked us down a flight of stairs and it took us a decade

to climb back up. But that won't do today. If COVID knocked

us down the stairs, our response was to leap--like some

superhero--up and out of the building. Only afterwards did

we realize we don’t know how to land.

Or how's this analogy -- to avoid a dangerous tangle on the

highway, we successfully accelerated around it -- only to

discover that our brakes aren’t working well.

You get the point. For the first time in decades, the

problem with the US economy is that it's running too hot,

with plentiful job opportunities driving unsustainable wage

growth and consumer demand keeping inflation above healthy

levels.

Fixing all this is mostly a job for the feds. But lawmakers

here in Massachusetts have an important role to play: they

need to adapt.

To start with a straightforward example, we need to stop

looking for policies that will create jobs. That goal is

simply futile with the Federal Reserve working hard to slow

the job market.

Instead, efforts to help workers and spur economic

development should emphasize skill-building and job

matching--so that less-educated workers and those held back

by discrimination can benefit from the surfeit of

opportunities. At the same time, we can help underperforming

regions of the state by copying place-based approaches being

successfully used in states like California.

Ultimately, though, the real challenge of this moment is far

broader. Over the last few decades, Massachusetts has passed

a host of major laws and regulations that made good sense at

the time but aren't well-suited for our current, overheated

economic environment. Recall the recent kerfuffle over state

tax rebates and 62F, and then imagine it splintered across

the policy landscape as other long-standing laws have their

unforeseen quirks exposed by a new economic reality.

Take Proposition 2½, a 1980s-era ballot initiative setting

strict limits on property taxes in cities and towns. Among

other things, Proposition 2½ says that property tax revenues

can't rise faster than 2.5 percent per year (with some

exceptions that we can set aside for simplicity sake.)

This cap made a certain kind of anti-tax sense when

inflation was muted and real estate prices were rising at a

steady, but not extravagant, pace. In those circumstances,

it acted as a meaningful but not debilitating check on local

taxes across the 351 cities and towns in Massachusetts.

But at moments of high inflation and tight labor markets --

like right now -- Proposition 2½ takes on a whole different

character. It doesn't just limit local tax growth; it forces

municipalities to actually cut taxes (in real terms) even as

it gets more expensive to hire municipal workers and

purchase construction materials.

Last year, real property taxes in Massachusetts fell 2.6

percent, the first decline since the early 1980s -- and

possibly the start of a worrisome pattern for Massachusetts

municipalities. And while the state could compensate cities

and towns for this lost revenue, that's hardly guaranteed.

Not to mention that if the state did use its own tax revenue

to backstop municipalities, the ironic effect would be to

transform Proposition 2½ from an effort to constrain taxes

into a mechanism for expanding the importance of Beacon

Hill's own, much more potent taxing authority.

Here's another example: health care costs.

Massachusetts has a well-established but weakly-enforced

target for health care costs, where spending per person is

not supposed to grow faster than 3.6 percent per year (the

exact benchmark varies but it’s never been higher than

this.) As with proposition 2½, it's a totally reasonable --

and justly celebrated -- way to limit health care cost

growth, provided that inflation and economic growth stay

within certain bounds.

But in overheated times like today, or economy-cratering

times like early 2020, our whole approach breaks down -- and

not just temporarily but for years.

To understand the issue, consider recent events. Health care

spending actually declined 2.4 percent in 2020, as COVID

lockdowns stopped all manner of elective and deferrable

treatment. That's obviously way below the 3.6 percent

benchmark. But it also sets up a weird problem, because when

you try to measure spending growth for 2021, you're starting

from this aberrant baseline. So your calculation will

inevitably show a huge increase in health care spending.

We don't yet have precisely comparable figures for

subsequent years, but other sources suggest state health

care spending increased around 8 percent in 2021 -- and then

another 7 percent through the first half of 2022.

Do these gyrating numbers tell us anything meaningful about

health care costs? Did we do something right in 2020 and

something terrible in 2021? Obviously not. They merely

reflect the limitations of our year-by-year approach to

health care cost when inflation is high and the economy in

turmoil.

And while it's tempting to shrug or share some patient

counsel about waiting for a return to normalcy, this isn't a

great alternative, as it leaves us blind to potentially

meaningful shifts happening right now. Plus, there's a

better response: with a different set of tools, our

monitoring system for health care cost growth could be made

to work, despite the weirdness of the moment (I won't bore

you but one place to start is to target levels rather than

rates of change.)

I could go on, but unfortunately there are too many

examples. Some of the pillars of state policy were built for

a very different economic world, one where inflation was

mild enough to be treated as background noise and job

creation was a driving challenge. But these pillars are

starting to crack; we'd be well served to fix some and

replace others.

— Evan Horowitz is the

executive director of the Center for State Policy Analysis

at Tufts University.

The Boston

Herald

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Question 1 out-raised, outspent all other statewide

campaigns combined

By Matthew Medsger

The choice that was placed before voters on whether to

levy an additional 4% tax on high incomes raised and spent

tens of millions more dollars this general election cycle

than all of the major party statewide campaigns for office

combined.

“Question 1 wasn’t just a regular law,” Fair Share Campaign

spokesman Andrew Farnitano told the Herald. “As a

constitutional amendment, it was a once-in-a-generation

opportunity to create a fairer tax system and fund decades

of greater investment in transportation and public

education.”

According to data provided by the Massachusetts Office of

Campaign and Political Finance, the campaign to pass

question 1, which passed by about 4 points, raised over

$32.2 million and spent about $28.5 million in 2022 to

convince residents taxing incomes over $1 million would

result in better roads and more successful schools.

The general election campaigns of candidates for governor,

lieutenant governor, state treasurer, attorney general,

secretary of the commonwealth and state auditor from the

Republican and Democratic parties raised, between the 11 of

them, just $11.6 million in 2022, according to OCPF.

The campaign against question 1 raised $14.4 million,

according to OCPF, also out-raising and outspending all of

the general election candidates.

“Tens of thousands of union members funded this

campaign with their hard-earned wages because they cared

deeply about improving our schools, colleges, roads, and

transit. And thousands of volunteers across the state spent

nights and weekends talking to their neighbors about

Question 1, because they wanted to see the ultra-rich

finally pay their fair share,” Farnitano said.

Even if the primary participants are added to the equation —

to include businessman Chris Doughty, who spent $2.5 million

of his own money on his bid for the Republican gubernatorial

nomination, and labor lawyer Shannon Liss-Riordan, who spent

$9.4 million of her fortunes only to lose the Democratic

nomination — the politicians combined still were out-raised

by the yes on 1 campaign, alone, by over $3 million.

According to figures from OCPF, the 19 Republican and

Democratic candidates who ran in a primary raised $27.1

million.

From its beginning, the coalition of labor, faith and

community organizations behind the Fair Share campaign,

Raise Up Massachusetts, has demonstrated the fundraising and

policy making power of grassroots campaigning, according to

Farnitano.

“Since the Raise Up Massachusetts coalition came together in

2013, we have nearly doubled wages for hundreds of thousands

of working people by winning two increases in the state’s

minimum wage, won best-in-the-nation earned sick time and

paid family and medical leave benefits for workers and their

families, and now, won permanent tax fairness to fund

education and transportation,” he said.

Governor-elect Maura Healey, aside from self-funded Liss-Riordan,

ran the campaign with the most cash, raising almost $5

million in 2022. Her running mate, Salem Mayor and Lt.

Governor-elect Kim Driscoll, raised $1.1 million.

Healey’s campaign, which held funds from her previous

statewide campaigns for attorney general, spent $7.4

million, according to the most recent information provided

by OCPF. Driscoll’s team spent about $860,000.

Their Republican opponents in the general election, former

state Reps. Geoff Diehl and Leah Cole Allen, raised $1.2

million and about $165,000. Their campaigns spent most of

the cash in 2022, according to OCPF.

Healey and Driscoll won the election by a more than 28-point

margin.

Attorney General-elect Andrea Campbell, who will take

Healey’s job as the top law enforcement officer in the

commonwealth in January, raised $2.3 million and spent $2.1

million, managing to win her primary despite just 25% of her

opponents’ funding.

Republican Jay McMahon, who ran unopposed in the Republican

primary for Attorney General, raised about $289,000 in 2022

and spent about $186,000. Campbell beat McMahon by a

25-point margin.

Incumbent State Treasurer Deb Goldberg, who ran unopposed in

both the primary and general election, still raised about

$209,000 in 2022 and spent about $382,000 using funds from

past campaigns, according to OCPF.

Secretary of State Bill Galvin spent almost $1.1 million to

defeat NAACP Boston President Tanisha Sullivan in the

primary and Republican Rayla Campbell in the General

Election.

State Sen. Diana DiZoglio beat investigator Anthony Amore to

take over the State Auditor’s office. Auditor-elect DiZoglio

raised about $521,000, compared to Amore’s about $259,000.

Question 2, which set a floor for dental spending, saw $10.1

million raised for it and $9.5 million against. Over 71% of

voters supported the idea that dental insurers should spend

more of premiums on dental care.

Question 3, which would have changed liquor license laws in

the commonwealth, did not pass, with 55% of voters opposed.

Proponents of the questions raised $1 million, the winning

opponents only $12.50, according to OCPF.

Question 4, which asked voters whether to keep a law passed

this summer, the Work and Family Mobility Act, or to

overturn it. 53.7% of voters thought that people who cannot

demonstrate lawful presence in the state should nevertheless

be allowed driver’s licenses. The law will take effect in

July.

Supporters raised $3.6 million, opponents, who gathered

the tens of thousands of signatures required to add the

question to the ballot, raised just $222,000.

Forbes

Magazine

Wednesday, November 9, 2022

Massachusetts Voters Approve ‘Millionaires Tax’

As Californians Reject An Income Tax Hike On High Earners

By Patrick Gleason

In the 2022 midterm elections, residents of California, like

those of Massachusetts, voted to put Democrats in commanding

control of their state government. Yet these two

left-leaning electorates rendered opposing verdicts on

similar tax measures seeking to raise state income tax rates

on upper income households.

With 57% voting No, California voters resoundingly defeated

Proposition 30, a ballot measure that would’ve added a new,