|

Help save yourself

— join CLT

today! |

CLT introduction and membership application |

What CLT saves you from the auto excise tax alone |

Make a contribution to support

CLT's work by clicking the button above

Ask your friends to join too |

Visit CLT on Facebook |

Barbara Anderson's Great Moments |

Follow CLT on Twitter |

CLT UPDATE

Saturday, March 18, 2017

"The Ticking Time Bomb" makes

Mass. #1

|

BARRY: I don't work for the state and so why

should I worry about whether my pension, the pension plan,

is funded for Connecticut there? Hey, I don't and none of my

kids work as a teacher so why am I worried about the status

of the pension plan in New Hampshire? Well you should be

worried if you pay taxes and own property because tax rates

are going to be impacted by unfunded and underfunded pension

plans.

Joining us now is Richard Johnson from the

Urban Institute. We're gonna talk about the New England

pension plan systems. Hi Richard, welcome to the show....

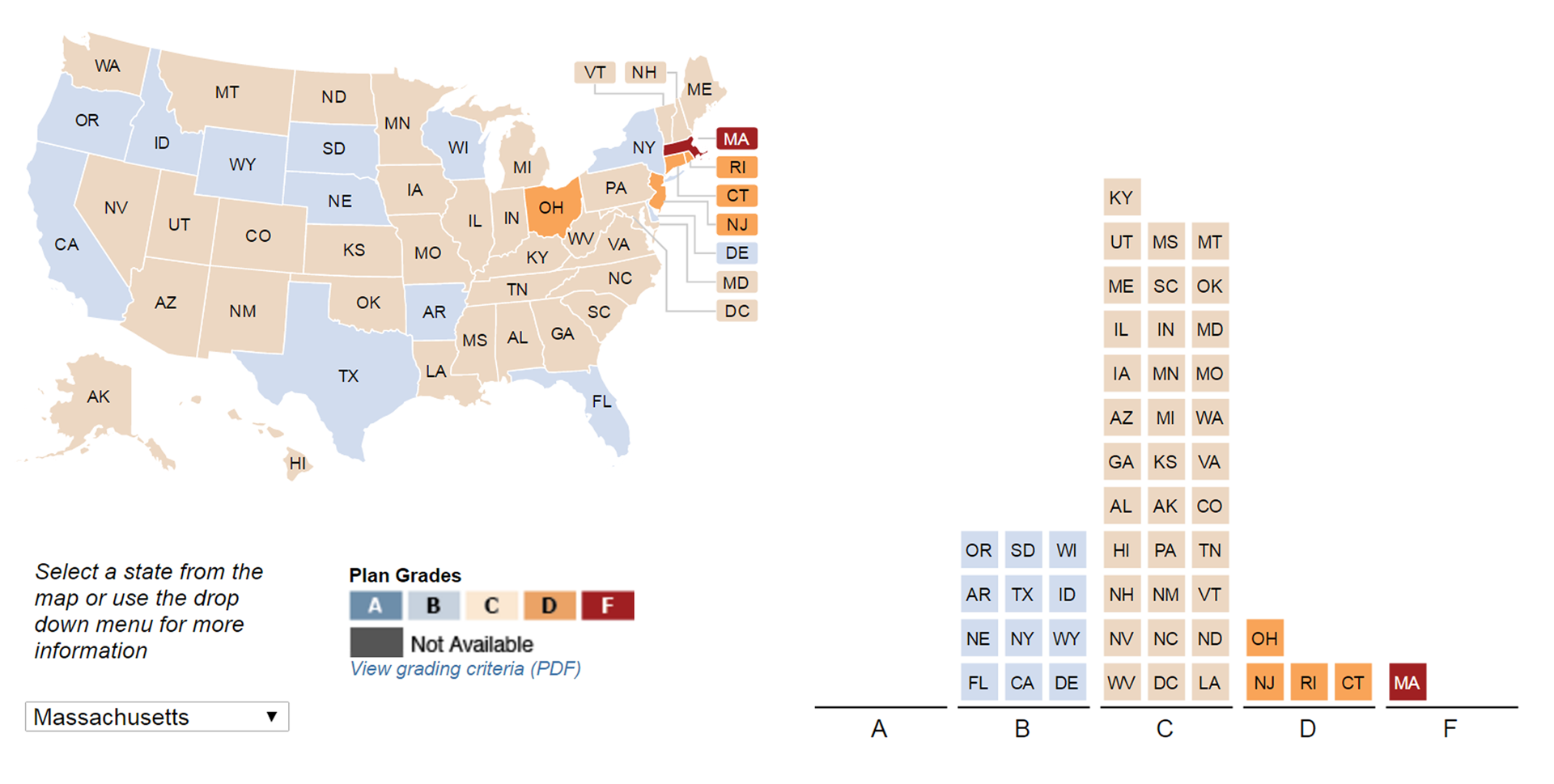

JOHN: Barry, only one state in the

country stood out like a sore thumb with an F; that was

Massachusetts. What's Massachusetts doing so wrong to be the

only state in the country to earn an F? Everything? ...

BARRY: Is it safe to assume that tax

rates in underfunded states are gonna go up? I'm looking at

the seven, the six New England states and I think the

highest grade you gave any of them was a C. And I looked at

that and I said if I'm, if I live in that state I have to

anticipate that either my income taxes, my property taxes,

or my sales taxes, or maybe all of the above are going to

increase in order to fund these obligations, because they

are in fact contractual obligations.

JOHNSON: That's right. You know we don't

know exactly how this is going to play out in terms of, you

know, if these plans really become insolvent what, what's

gonna happen. But the state constitutions generally guarantee

employees that, that the benefits that they have earned have

to be paid. And, and so I think it right, I think we're gonna see some big tax increases in the future.

WRKO - The Financial Exchange

Barry Armstrong

Monday, March 12, 2017

Urban Institute, New England Pension Plans

Urban Institute

The State of Retirement: Grading America's Public Pension

Plans

There will also be a $2.395 billion transfer

to the state pension fund

—

an increase of $196 million over the fiscal 2017

contribution

—

which is expected to keep Massachusetts on track to fully

fund its pension liability by 2036.

"The decision to devote increased resources

to maintain the current pension schedule demonstrates fiscal

responsibility," [Rep. Brian Dempsey, House chairman of the

Ways and Means Committee] said in the statement. "This

agreement allows us to begin the FY18 budget process and

balances the investments of today with a commitment to

meeting our long term future spending obligations."

State House News Service

Thursday, January 12, 2017

Beacon Hill budget leaders agree on projected FY18 revenue

growth

Massachusetts has committed to paying more

than $15 billion over the next 30 years for health insurance

for its retirees. But the state has set aside almost none of

the money needed to pay for it.

Talk of reform under former governor Deval

Patrick, a Democrat, went nowhere. Budget proposals by Gov.

Charlie Baker, a Republican, and the Democratic-controlled

House would not make a dent in the unfunded liability.

"Each year we delay action on this, the

problem gets bigger and more unwieldy," said Carolyn Ryan,

assistant director of policy and research for the

business-oriented Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, which

has studied the impact of retiree benefits on state and

local governments.

In fiscal year 2014, the state owed $15.6

billion in future health insurance benefits, which must be

paid out over the next 30 years. The state had only set

aside money to pay for 3.3 percent of that, leaving an

unfunded liability of $15 billion, according to state

financial documents....

Until recently, Massachusetts funded these

other post-employment benefits (OPEB) at the amount that

needed to be paid out that year - not the far larger amount

of costs that were being accrued that year to be paid in the

future. In the last decade, national accounting standards

changed to require governments to calculate the amount they

committed in future benefits. So Massachusetts learned, for

example, that in fiscal year 2013, it budgeted $415 million

for retiree health care costs, while employees were accruing

$1.3 billion in benefits.

The issue is similar to one facing the state

employee pension system, which state officials often talk

about the need to fund. But the pension system is better

funded. As of 2014, the pension fund had money to pay for 70

percent of its $30 billion liability. It is expected to be

fully funded by 2040....

In his 2016 budget, Baker was supposed to

set aside $112 million for OPEB, based on a funding

schedule, but he proposed instead freezing payments at $85

million, giving him more money to spend on current operating

expenses.

"We are definitely considering OPEB reform,"

said Dominick Ianno, chief of staff at the Executive Office

of Administration and Finance. "Unfortunately, in the

context of a $1.8 billion budget deficit that we inherited,

this wasn't the year we were able to accomplish reform in

this area."...

[Carolyn Ryan, assistant director of policy

and research for the business-oriented Massachusetts

Taxpayers Foundation] said Massachusetts' costs are high

because the state has generous eligibility requirements and

high health care costs.

Ryan said taxpayers should be worried about

the liability. "These are not what ifs. These are actual

bills that we've already incurred," Ryan said. "Over the

next 30 years, we're going to be paying out $16

billion....You won't be able to spend that money on

education, transportation and other things."

The Springfield Republican

April 24, 2015

$15 billion - What Massachusetts needs

to pay retiree insurance benefits for 30 years, but doesn't

have

|

|

Chip Ford's CLT

Commentary

I do a lot of reading, watching, and listening every day for

news and information that affects us taxpayers

— a whole lot.

This is necessary so that data of particular interest can be

accumulated for our use, so we know what's happening and can

keep you informed. That's the easy part.The

challenging part is being able to remember all the factoids

I come across seven days and nights every week, then

recognize and target the connecting multitude of random

points. I love those "Eureka!" moments when my process

pays off. This is one of those.

While performing my ritual morning news sweep on Monday,

I had WRKO's "The Financial Exchange" with Barry Armstrong

playing in the background on the radio. When he

announced that his next guest from the Urban Institute would

explain how Massachusetts ranked at the very bottom in the

nation with the most egregious government employee pension

liability crisis it caught my attention. [See

link below to listen to this program segment.]

I recalled the (above) mention of how much of the

governor's proposed $40 billion budget would be devoted to

funding the problem (over $2 billion of it). That

supposedly would lead to a fully-funded state pension system

in two decades — by

2036.

Massachusetts, we're Number One again: The worst

government employee pension liability in the nation!

And that doesn't include the additional $15

billion owed to government employees for their

health-insurance-for-life benefits.

We taxpayers are on the hook for decades of inexcusable

mismanagement and misplaced priorities as Beacon Hill

politicians found other ways to spend our money

— like obscene pay raises for

themselves.

CLT has long-advocated for reform of overly-generous

public employee benefits. We created an entire project

of it from 1999 to 2011, repeatedly warned about "The

Ticking Time Bomb" of unfunded, underfunded, and

overly-generous government employee retirement benefits:

Click above graphic to

enter

INTRODUCTION (1999)

As economic cycles rise

and fall, only public employee benefits always

increase.

As the private sector cuts

costs and employee benefits to survive, public

employee benefits only increase.

Whether property values

rise or fall, public employee benefits always

climb.

Nationally, public employee salaries and

benefits now exceed those of the private sector

by 50 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics.

These overly-generous

entitlements have for too long been falsely

termed "fixed costs." They are "fixed" by

politicians negotiating with public employee

unions. "Fixed" is the right word only as in

"the fix is in."

The only way to continue

supporting public employee unions' ceaseless

demands and their steadily escalating salaries

and benefits is through higher taxes or with

drastically reduced core government services

year after year. Every cent that goes to their

luxuries comes directly from strapped tax-paying

family budgets. Taxpayers are receiving fewer

and less basic government services as public

employees get fatter at the trough.

The end of this continuum is

arriving, one way or the other.

Taxpayers have run out of money

. . . and patience. The bill is coming due, and

the politically promised money just isn't there

—

by a long shot.

We're tired of this

taxpayer-funded double standard. We're fed up

with working harder and longer and being taxed

more for less just to support the grand

lifestyle to which public employees have become

accustomed.

This system of abuse and its

unconscionable sense of entitlement is about to

crash and burn if it isn't very quickly

reformed. When under its own weight it

inevitably does, there simply won't be enough

taxpayers to further victimize to pay for its

unimaginable cost. We will have been tapped

dry, bankrupted. All of us. And with us, so

too will be the greedy public employees with

their unfunded promises

— all victims of political expedience.

This end is not far off, and the

juggernaut plods steadily toward us. It will

arrive sooner or later. If nothing is done to

correct past largesse at taxpayers' expense, it

will arrive sooner. In some places it already

has.

Despite our best efforts and those of others to play the

role of the Paul Revere of the Pension Crisis, Massachusetts

is now rated the most indebted state in the nation, at the

bottom of a very deep barrel of government employee pension

liabilities. It's good to see that the governor

recognizes this looming doomsday crisis and is trying to

dampen its impact, but why are we in this crisis when

budgets have increased at a rate of a billion-dollars-a-year

for over a decade? Gov. Baker now wants to throw

$2.395 billion into the gaping hole —

but even with that huge payment it will still take taxpayers

almost two decades to pay down the Beacon

Hill-imposed liability.

It is those very same Beacon Hill pols

— "The Best

Legislature Money Can Buy" — who dug us into this

crisis who then had the audacity to just reward themselves

with a huge pay raise

— which

of course adds to their pensions

— which

in turn adds to the taxpayers' burden for at least another

generation.

|

|

|

|

WRKO - The Financial Exchange

Barry Armstrong

Monday, March 12, 2017

Urban Institute, New England Pension Plans

08:04 minutes

—TRANSCRIPT—

BARRY: I don't work for the state and so why

should I worry about whether my pension, the

pension plan, is funded for Connecticut there?

Hey, I don't and none of my kids work as a

teacher so why am I worried about the status of

the pension plan in New Hampshire? Well you

should be worried if you pay taxes and own

property because tax rates are going to be

impacted by unfunded and underfunded pension

plans.

Joining us now is Richard Johnson from the Urban

Institute. We're gonna talk about the New

England pension plan systems. Hi Richard,

welcome to the show.

JOHNSON: Hi, thank you very much for having me.

BARRY: We're glad to. So can you give us what

you're grading criteria was for pension plans? I

was reading the report, I think was last

Thursday when I came across it. But how did you

come across the grades? New England didn't do

particularly well.

JOHNSON: No it didn't. So we had three broad

categories. We looked first of all at the

retirement security that the plans provided at

the state and local levels. That's a crucial

part of the function of retirement plans and

it's supposed provide income in retirement

writing com. In retirement of older people when

it will put on that metric that may look at the

funding. How well I'd these promises funded and

is likely that this state and local government

can meet these funding obligations? . . .

@ 3:57

JOHN: Barry, only one state in the country stood

out like a sore thumb with an F; that was

Massachusetts. What's Massachusetts doing so

wrong to be the only state in the country to

earn an F? Everything?

JOHNSON: You know it's pretty much everything.

It was bad funding, it was as of two years ago

that they weren't making their required

contributions at that point, and the structure

of that, they had high employee contributions

which meant that, because employees had to

contribute so much of their pay check into the

plan each year it was very hard for them to get

anything back from the plan. It was particularly

bad for younger workers who would not, really.

unlikely to get really much out of the plan at

all. And it also in Massachusetts, like

Connecticut, and like Maine, at least

Connecticut teachers and Maine, are those states

employees are not covered by Social Security and

that makes it harder to get a really secure

retirement out of the plan.

BARRY: It sure does Richard, it sure does. Is it

safe to assume that tax rates in underfunded

states are gonna go up? I'm looking at the seven,

the six New England states and I think the

highest grade you gave any of them was a C. And

I looked at that and I said if I'm, if I live in

that state I have to anticipate that either my

income taxes, my property taxes, or my sales

taxes, or maybe all of the above are going to

increase in order to fund these obligations,

because they are in fact contractual

obligations.

JOHNSON: That's right. You know we don't know

exactly how this is going to play out in terms

of, you know, if these plans really become

insolvent what, what's gonna happen. But the

state constitutions generally guarantee employees

that, that the benefits that they have earned

have to be paid. And, and so I think it right, I

think we're gonna see some big tax increases in

the future.

Now what could happen, you know it's possible

that others services could be cut and then that

could free up some funds to go into the pension

plan, but either way, taxpayers, the residents

of the state, are going to bear some costs,

either through reduced services of higher taxes.

BARRY: Richard thank you very much for your time

we appreciate it. Richard Johnson from the Urban

Institute, and John, I can tell you. You go into

town meetings, you go into city legislatures and

you listen to the agenda items and one of the

big items on every town's mind is "Gee, we owe a

lot of money to our retired teachers,

firefighters, and police.

JOHN: And you know at some point these

constitutions may have to be amended. If that,

if the situation gets so dire the cities and

towns will have to go to these unions and say,

look we don't have the money.

BARRY: I don't think they'll do that. I think

what they'll do is say to future generations,

John, we have to cut these pension plans out.

JOHN: Oh no question . . .

BARRY: Like the private sector did. I mean when

you began your career did you have a pension

plan?

JOHN: No.

BARRY: No? I did.

JOHN: Actually I had one, yeah, and I got bought

out of it for like five years.

BARRY: Back in the seventies and eighties when

we began our careers, at least that's when I

began mine, you had pension plans in the private

sector. I think what's gonna happen is they'll

be a tax rebellion among Tucker's generation,

Tucker's generation's going to be one that wises

up and says enough already, my property taxes

are going up like crazy and they're gonna say

"Get rid of these defined benefit pension plans.

We can't afford them." And at least then you

stop the bleeding. But we haven't even had that

discussion yet.

JOHN: When you look at the grading that was done

in this report, the worst category is providing

retirement income for short term employees.

Short term and long term employees gonna need to

think together, that participating in like 401K

programs is something you gonna have to do.

BARRY: Yes think about a lot.

The Springfield Republican

April 24, 2015

$15 billion - What Massachusetts needs to pay

retiree insurance benefits for 30 years, but

doesn't have

By Shira Schoenberg

Massachusetts has committed to paying more than

$15 billion over the next 30 years for health

insurance for its retirees. But the state has

set aside almost none of the money needed to pay

for it.

Talk of reform under former governor Deval

Patrick, a Democrat, went nowhere. Budget

proposals by Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican,

and the Democratic-controlled House would not

make a dent in the unfunded liability.

"Each year we delay action on this, the problem

gets bigger and more unwieldy," said Carolyn

Ryan, assistant director of policy and research

for the business-oriented Massachusetts

Taxpayers Foundation, which has studied the

impact of retiree benefits on state and local

governments.

In fiscal year 2014, the state owed $15.6

billion in future health insurance benefits,

which must be paid out over the next 30 years.

The state had only set aside money to pay for

3.3 percent of that, leaving an unfunded

liability of $15 billion, according to state

financial documents.

The basic problem is that the cost of providing

health insurance to public retirees is

increasing faster than Massachusetts is setting

aside money to pay for it.

Massachusetts provides health insurance, life

insurance and prescription drug benefits to

public retirees and their families, with copays

and deductibles similar to those in private

plans.

Until recently, Massachusetts funded these other

post-employment benefits (OPEB) at the amount

that needed to be paid out that year - not the

far larger amount of costs that were being

accrued that year to be paid in the future. In

the last decade, national accounting standards

changed to require governments to calculate the

amount they committed in future benefits. So

Massachusetts learned, for example, that in

fiscal year 2013, it budgeted $415 million for

retiree health care costs, while employees were

accruing $1.3 billion in benefits.

The issue is similar to one facing the state

employee pension system, which state officials

often talk about the need to fund. But the

pension system is better funded. As of 2014, the

pension fund had money to pay for 70 percent of

its $30 billion liability. It is expected to be

fully funded by 2040.

The state has made efforts to fund OPEB. It set

up a $350 million fund in 2009, and has been

paying into it each year. State officials

committed to dedicating an increasing portion of

payments from a settlement with tobacco

companies. The tobacco payments are projected to

increase from $56 million in fiscal year 2014 to

$250 million by 2023. A percentage of capital

gains tax revenue above a certain threshold also

pays for OPEB. But the cost of providing

benefits increases annually, so by 2023, the

state would still be funding only around half

its yearly obligation, according to projections

in a state financial report.

In his 2016 budget, Baker was supposed to set

aside $112 million for OPEB, based on a funding

schedule, but he proposed instead freezing

payments at $85 million, giving him more money

to spend on current operating expenses.

"We are definitely considering OPEB reform,"

said Dominick Ianno, chief of staff at the

Executive Office of Administration and Finance.

"Unfortunately, in the context of a $1.8 billion

budget deficit that we inherited, this wasn't

the year we were able to accomplish reform in

this area."

Baker proposed requiring some employees to pay a

higher percentage of their health care premiums,

which would lower the liability in the long term

because it would affect how much those employees

pay for health care when they retire. But facing

resistance from state employees, the House Ways

and Means Committee scuttled that plan in its

version of the budget.

Massachusetts is not unusual. A 2012 report by

the Pew Center on the States found that states

had set aside just 5 percent of the money they

needed to pay for health insurance and other

retiree benefits. Seventeen states had no money

set aside, and only seven funded at least 25

percent of their liability.

A report released in December by the Center for

State and Local Government Excellence found that

the mean unfunded OPEB liability per state was

$10 billion, and the median was $2 billion.

Massachusetts had the ninth highest unfunded

liability among all 50 states.

Ryan said Massachusetts' costs are high because

the state has generous eligibility requirements

and high health care costs.

Ryan said taxpayers should be worried about the

liability. "These are not what ifs. These are

actual bills that we've already incurred," Ryan

said. "Over the next 30 years, we're going to be

paying out $16 billion....You won't be able to

spend that money on education, transportation

and other things."

In 2013, a state task force recommended changes

to OPEB, including increasing the age and years

of service required to be eligible for coverage

and prorating benefits based on years of

service. Patrick proposed legislation that would

have made some of these changes. But public

sector unions protested the changes, which they

said would break promises made when employees

were hired. The bill did not pass.

State Rep. John Scibak, D-South Hadley, served

on the OPEB commission. Scibak said the issue of

pension funding has historically gotten more

attention than OPEB funding, even though the

pension system is in better shape. "It

definitely is an issue and a concern, and it's

one that has not historically gotten sufficient

attention from the commonwealth or from

municipalities," Scibak said.

Part of the problem, Scibak said, is spending

money to hire police officers or social workers

has a tangible political benefit, while no one

would see the impact of spending money to

pre-fund retiree health benefits. But Scibak

pointed out that OPEB costs will continue to

rise as long as people continue living longer

and health care costs continue to increase,

which has been the trend in recent years. Paying

for this will squeeze state spending in other

areas.

One difference between pension and OPEB reform

is that Massachusetts courts have determined

that pensions are contractual benefits, so they

cannot be changed once an employee is hired.

Retiree health care is not protected in the same

way, so the state could potentially change

benefits or contribution rates.

Shawn Duhamel, legislative director of the

Retired State County and Municipal Employees

Association, said he believes the Legislature

will reconsider OPEB in some way. "The issue of

OPEB isn't going to go away. A solution needs to

be found," Duhamel said.

Duhamel wants government to focus on controlling

health care costs, rather than cutting benefits

or forcing retirees to pay more. "The overall

problem with health care isn't who's paying the

bills, it's the cost of the product in the first

place," Duhamel said. "Without addressing the

cost of health care and the root of the problem

first, you're essentially rearranging the deck

chairs on the Titanic."

State Treasurer Deborah Goldberg said the

unfunded OPEB liability "remains a concern." "I

will continue to work with the Governor, our

legislative leaders and labor on ways to more

effectively address the issue," Goldberg said in

a statement.

Jared Magee, a researcher for the Legislature's

Joint Committee on Public Service, said the

committee has not yet identified priorities for

the coming session. Magee said there have been

no bills filed similar to the one filed by

Patrick in 2013. But OPEB reform is one of the

major issues the committee deals with each

session. "The matter of pension liability and

OPEB liability is not going to go anywhere until

we deal with it," Magee said. "But at least at

this early stage in the game, we have no plans

yet." |

| |

NOTE: In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this

material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior

interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes

only. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

Citizens for Limited Taxation ▪

PO Box 1147 ▪ Marblehead, MA 01945

▪ 508-915-3665

BACK TO CLT

HOMEPAGE

|