“Today, over 100

million Americans — about one-third of the population — can trace

their ancestry to the immigrants who first arrived in America at

Ellis Island before dispersing to points all over the country.”

— Wikipedia

I am one of those 100

million Americans. My paternal grandparents came here from Croatia,

which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; my maternal

grandparents were descended from earlier Irish and German

immigrants.

I’d always been taught

that immigrants were processed at Ellis Island. So, I was startled

when I heard some people say, during the current debate about

illegal immigration, that most early immigrants also entered the

country illegally, wherever they could get ashore, that Ellis Island

was open for only a few years. That didn’t sound right, and it

wasn’t.

In reality, more than

70 percent of all immigrants entered through New York City:

initially, at the Castle Garden depot near the tip of Manhattan,

then at the new detention center at Ellis Island from 1892 to 1954.

(Those coming from Asia were processed in San Francisco.)

And, relevant to the

current discussion, you should know what Wikipedia tells us:

“Generally, those

immigrants who were approved spent from two to five hours at Ellis

Island. Arrivals were asked 29 questions including name, occupation,

and the amount of money carried. It was important to the American

government that the new arrivals could support themselves and have

money to get started. The average the government wanted the

immigrants to have was between 18 and 25 dollars. Those with visible

health problems or diseases were sent home or held in the island’s

hospital facilities for long periods of time. More than three

thousand would-be immigrants died on Ellis Island while being held

in the hospital facilities. Some unskilled workers were rejected

because they were considered “likely to become a public charge.”

About 2 percent were denied admission to the U.S. and sent back to

their countries of origin for reasons such as having a chronic

contagious disease, criminal background, or insanity.”

So, most of us are

descended from the best: those courageous enough to leave familiar

countries and customs, relatively healthy risk-takers who had some

skills to offer their new home. The Library of Congress notes that

“Fleeing crop failure, land and job shortages, rising taxes, and

famine, many came to the U.S. because it was perceived as the land

of economic opportunity. Others came seeking personal freedom or

relief from political and religious persecution. With hope for a

brighter future, nearly 12 million immigrants arrived in the United

States between 1870 and 1900.”

| |

|

|

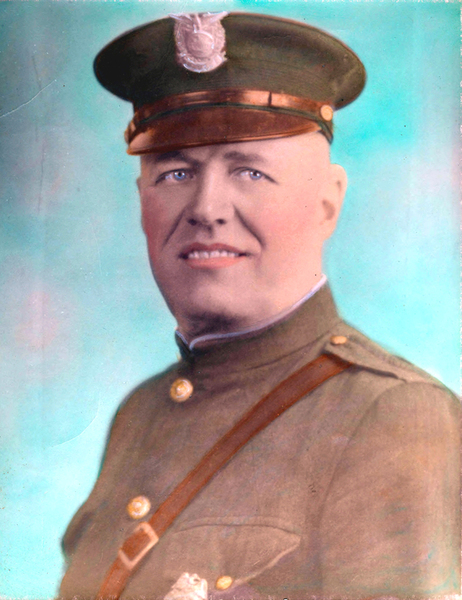

Barbara's

Croation-American grandfather was a policeman until he

arrested the mayor. |

Now we’re told that

roughly 12 million were living illegally in the U.S. in 2007, and we

know it’s many more today. Our country used to limit the flow so

that new citizens could have time to assimilate before another group

joined them; now there is no processing, just an open invitation for

even more to come, regardless of job skills, health and planned

assimilation.

I was named for my two

grandmothers, one German, one Croatian. The former was born in

Pennsylvania; her mother was born in Bavaria. A cousin tells me that

our German great-grandfather was a carpenter who built homes for his

two daughters a block apart in my hometown of St. Marys, which had

been founded by German immigrants in 1842. My mother grew up in one

of the houses with her four sisters.

Their great-great

grandmother’s family had emigrated to Ireland from France in the

12th century. She emigrated to St. Marys in 1884. Other family

members emigrated to Bergen, N.Y., apparently having passed the

tests at Ellis Island.

Like many Irish, they

worked on the railroad. My granddad, who married Barbara and

inherited the house, was train master for the Shawmut Line. They

lived a comfortable middle-class life.

|

|

|

Barbara's

Croatian-American grandfather, with his two

first-generation children, her father Max on the right. |

My Croatian

grandfather, age 15, emigrated in 1907, the peak year of European

immigration. By 1910, 13.5 million immigrants were living in the

United States, according to Wikipedia. I’ve been told that his

father lived in America, returned to Croatia and sent his son here

from their farming community near the Slovenian border. From what he

told us, he didn’t fill one of the above requirements, having only

18 cents in his pocket when he arrived, but his size must have

caught the attention of those who were seeking strong peasants for

jobs in the Pittsburgh steel mills.

He was naturalized in

1924; he eventually settled in St. Marys, part of a small community

of Slavic peoples. In my hometown, the three ethnic groups shared a

Catholic heritage and seemed to get along well enough for his

first-generation son to marry my Irish-German-American mother; they

lived happily-ever-after, going dancing every Saturday night.

My grandmother Barbara,

however, died young during the Spanish flu epidemic. Grandpa was a

policeman when I was born, until he arrested the town’s mayor for

public drunkenness, after which he was fired, a family story that

I’m sure helped create my own political views. Gramps didn’t mind;

he went to work as a security officer on the Erie docks and

eventually returned to St. Marys to run Big Mox’s, his second wife’s

family pub, which I remember he seemed to enjoy.

He spoke excellent

English and was a leader in the Slavic community; he paid for my two

years of college, and when he died, he left enough money for my dad

to realize his dream of owning a small hardware store. And this, my

friends, is the American immigrant experience in a nutshell.

Grandpa’s two brothers

emigrated to Canada, perhaps during the period that Slavs weren’t

allowed to enter the U.S. His niece Zorah later escaped from what

had become communist Yugoslavia; Grandpa went to New York City to

get her. I was old enough then that I remember the stories she told

us about living under communism — another influence on my present

worldview.

I am grateful that my

direct Irish family survived the potato famine, that the Germans

weren’t still in Bavaria when Hitler came to power, that Grandpa

left Croatia before Tito became dictator. Gramps told me that they’d

fought as boys in the schoolyard, and this was one reason he wasn’t

going back for a visit to his village.

Thank you, America, for

accepting my legal immigrant family.